Acton

Acton, Cheshire

Simon Jenkins gave this church a single star, mentioning his beloved monuments but somehow overlooking the Norman font and decorative carvings. Not for the first time I wonder if he was amnesiac or whether he didn’t visit at all. Mind you, I do have a theory why he so often excludes items that seem quite significant: he used Country Life photographs for his book. If he had taken dozens of his own photographs as I do then he would have remembered better.

That said, every photograph on this page is by my partner in church crawling, Bonnie Herrick. A computing problem managed to wipe all mine. So there are not many exterior shots because her focus (pun intended) is more on the art within. But most of the pictures are identical to the ones I lost - just better-focused by Ms Meticulous.

Acton is mentioned in the Domesday survey as having priests. There was probably then a church of pre-Conquest foundation. Until Hastings it was held by Earl Morcar, a prominent Anglo-Saxon noble who fought against Tostig and Harald Hardrada’s invasion in 1066. It would be unsurprising then if it was a stone church and that the collection of early sculptures in the south aisle are its legacy. The font too is thought to be Norman but as with those sculptures that is at least open to question.

The lowest part of the tower with its lancet windows is clearly in late twelfth or early thirteenth century Early English style. The north arcade and the chancel arch are from the fourteenth century but Victorian remodelling has robbed them of their mediaeval character. The upper parts date from 1759 after a tower collapse.

The chancel dates only from the seventeenth century/ This was the gift of the Wilbrahim family in 1633. A large scale restoration by Paley & Austin - prominent and northern church Victorian builders and restorers - produced most of the nave you see today.

The font is from the naive tradition of Norman sculpture a circular piece with crude figures and stylised decoration. The ancient stones in the south aisle are the most fascinating pieces here. They seem to have been carved by the same sculptor and, curiously, nobody seems to have much idea of where they were originally placed. Arcading decoration on one or two stones point towards an early post-Conquest date but it is certainly true that the figure carving is off indeterminate age and could as easily be pre- as post-Conquest. We must say on the balance of probability that the collection - with at least one exception - is likely but not certain to be Norman.

The church is very much in the Cheshire tradition of large sandstone building, mainly in the Perpendicular style. Acton stands out for its sculptures and monuments inside. Better still, it is just over a mile from the large town church of Nantwich with its extensive misericord range. If you visit one you really will be missing out if you don’t visit the other.

Looking east towards the chancel. Note the pretty pink hue from the sandstone. The chancel arch is fourteenth century and its width gives an airy openness to the church. The aisles have been raised although the capitals were possibly re-used. Both the seventeenth century chancel and the east end of the south aisle are lit by large Perpendicular style windows,

Four faces of the naively-decorated probably Norman font. Standing figures and stylised decoration sit beneath rounded arcade mouldings. It is certainly crude, somewhat stylistically similar to the other carved stones in the church and if it Norman it is probably from the eleventh century rather than the twelfth century. It is a familiar story for ancient fonts that this was used as a pig trough on a local farm. Then it served as a flower bowl in nearby Dorfold Hall until 1897!

Left: The stack of six stones at the end of the south aisle. They were found built into the low “bench” around the walls of the church. But where were they originally? Being quadrilateral in shape they could not have been part of a Norman doorway. They are the wrong shape and size for arch capitals. Moreover the top block is decorative rather than figurative and the bottom two appear to have been adjacent or originally a single block. And the decorative block at the top is intriguing. It was clearly one of at least a pair of stones: it does not stand alone as a design. Right Upper: Christ gives a benediction flanked by two other figures. The eyes (often a good pointer) and the roundness of the face are reminiscent of the faces on the font. Right Lower: The decorative stone. The bottom edge was clearly attached to another block or was part of a larger block. Even more speculatively were they part of a churchyard cross? That decorated stone certainly fits the bill. The fact is that apart from the bottom two blocks these could all have been originally arranged vertically and could as easily be pre-Conquest as post-Conquest..

The four lower blocks of sculptured stone. The upper left figure appears to be a bishop with his crozier. We can’t tell who the right hand figure is but note that his head is missing and the original design must have been taller than this block. We must assume they were part of a larger sculptural scene and were “rescued” from its destruction. Was it a carved frieze of some sort? The bottom two blocks were originally either contiguous or part of a longer composition. They are wider than the other blocks so not, therefore, part of any putative vertical decorative feature. It is all a mystery because the fact is I know of no surviving Norman frieze. But there are plenty of Anglo-Saxon churchyard crosses. It is probably a mistake to make assumptions about all of these blocks being from the same date or of the same composition. But I think most commentators do make that assumption.

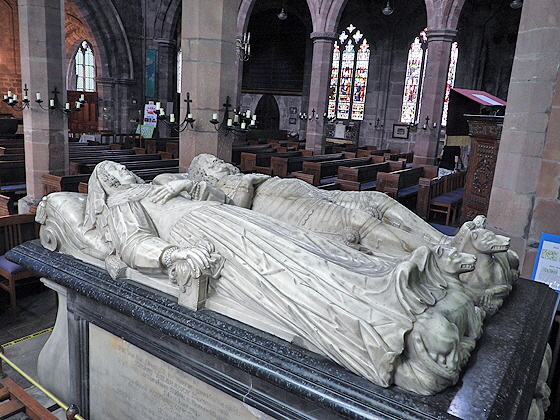

Left: This piece is reckoned by CSBI to be an impost block (that is, one which connects the sides of a doorway to its arch, usually through the whole depth of the wall. This, again, is interesting because impost blocks are rather more usual (although not unique to) Anglo-Saxon doorways. And these faces look decidedly Anglo-Saxon in style, Overall, I am definitely of the view that no conclusions can be drawn about the ages of these blocks, nor that that they are of a single period and certainly not that these were all part of a single decorative scheme or artefact. So they must remain a mystery as must the whole early history of this church. Right: The recumbent effigies of Richard Wilbrahim (d.1643) and his wife. Wilbrahim was responsible for the seventeenth century chancel and much external adornment including the elaborate parapets.

Imagery of the the Richard Wilbrahim monument. Wilbrahim died shortly after the start of the Civil War.

The impressive monument to William Mainwaring (no relation to Captain Mainwaring!) who died in 1399. His head is on a rather odd horse’s head; at his feet a lion. At the top of the monument is the head of an ass, A previous Mainwaring had a horse killed beneath him and mounted an ass to join the charge. (Thank you, Simon Jenkins). Is that, in fact, an ass’s head on which William rests his head (right), rather than on that of a horse?

Left: The Jacobean pulpit. Right: I was very taken with this unusual door to the tower stairway and its equally odd steps,

Left and Centre: Two Flemish stained glass roundels of the seventeenth century, perhaps brought here by Richard Wilbrahim. Right: Carved decoration on the west door.