Cley-next-the-Sea

Cley-next-the-Sea, Norfolk

Cley (pron “Cl-eye”) is perhaps best known for its huge iconic windmill and as a mecca for seabird and waterfowl watchers. Since I first knew it, this part of Norfolk has become a honeypot for second-homers but Cley retains all of its original charm. “Next-the-Sea” is telling. Centuries ago - if they had used such monikers - it would have been “on Sea”; because Cley was a thriving port. Many is the English town that has that story to tell. Boston in Lincolnshire was one of the biggest ports in England with wealth (and a church) to match. Romney in Kent is another that comes to mind. We are used to thinking of Liverpool, Bristol, Southampton and, of course, London and the like as being our great ports. But in mediaeval England our main trade was with Europe, especially the low countries, and so many of our largest ports faced east and south, not west.

As trade became more worldwide and there were more commodities to trade, especially with the New World, those west coast ports grew like topsy, diminishing many of the mediaeval ones. The other factor, however, as here at Cley was changing physical topography. In mediaeval times river transport was all-important given the absence of a credible road structure so many ports were located on estuaries of rivers. Climate change (not a new concept) and other environmental interactions very often led to the silting up of the very rivers that gave some ports their raison d’etre. Coastal erosion (still a problem in Norfolk) was a factor. In other places such as Romney storms could cause catastrophic and irreversible changes in river courses and coastlines.

So when you look at the magnificent church at Cley and are wondering how this tiny community could support such an edifice, you now know! This was a rich place. Much of that wealth, of course, was in the hands of the rich few. Much of what we see now was built before the Black Death of 1348-50 which gradually sounded the death knell of serfdom. Wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few. The south porch here is early fifteenth century and the rich families left their coats of arms all over it.

As you would expect, there was an earlier church than that which we see today. This would have been much smaller and located roughly where the north aisle sits today. This explains why the west tower is in fact on the north west of today’s church. Towers were too massive to be easily and affordably replaced. Sir John de Vaux whose family had acquired estates after the Conquest was granted land here by Henry III in 1265 to add to his holdings around Boston. When Sir John died his two daughters married into the de Roos and de Nerford families so that from 1288 thee two families became the patrons of the church. A new chancel was built around that time and was much as we see it today. From about 1315 the building of today’s nave was undertaken as was the building of transepts to north and south. The magnificent Perpendicular style south porch followed in 1405-14, the church’s historians being able to date this from the extensive heraldry. It follows that he south aisle must pre-date it. The west front dates from the 1340s. Between 1430-40, as was so commonplace throughout England, cheaper glass and the craving for more light led to the very ornate clerestory.

Superb as the architecture is, for those with the eyes to see, it is the mediaeval art which sets this church apart. It is immediately obvious in the highly decorated face of the south porch. Less obvious and much more entertaining are the roof bosses of the porch ceiling where we can see two monks (?) tanning the hide of a boy and a particularly detailed scene of a housewife chasing away a fox who has made off with one of her geese. Better still in the spaces at the junctions of the arches of the south aisle (the “spandrels”) are sculptures that for their size and detail can hardly be matched in any parish church. They are particularly unusual in East Anglia where lack of quarry stone caused artistic invention to rest with the carpenters rather than with the stonemasons. They even have goodly traces of paint! On the south side of the south aisle there are more carvings, at least one of which is also - ahem - rather rude. The benches have a number of entertaining poppy heads. There is a mid-fifteenth century Seven Sacraments font such as are fairly common in East Anglia but more or less confined to the area.

It is a church that I would call a “Church Crawlers” church: one which is full of little gems and items of interest. Cley, however, can add magnificence to its attributes.

Left: The south west corner of the church. Right: The view to the east inside the church. On the face of it, the interior is unexceptional but there are many treasures to be found.

Left: The south porch is a masterpiece of Perpendicular architecture. Although you can see that the south aisle to which it is attached is constructed of flint and rubble, this being quarrystone-deprived Norfolk, no expense has been spared in acquiring ashlar for this showpiece of the patrons’ family lineage, Shields and religious symbolism surround its doorway and within its spandrels. In most East Anglian churches this porch would have been flint and the patrons would have settled for “flushwork” designs made from small pieces of stone set into the flint. The statue within the niche, of course, is a modern replacement for what was removed after the Reformation. There are still-empty niches to left and right, two on each side. It is a two story structure providing a “parvise” room above the porch. It probably housed the priest at some point. What Pevsner described admiringly as near filigree battlements are indeed gorgeous examples of the stonemason’s art. Right: The west doorway is in fourteenth century Decorated style. It has multiple courses of masonry and is inset with ogee arches with a distinctive Moorish look. The king and queen are Edward III and Phillipa of Hainault.

Left: Part of the decorative course of the south porch doorway with coats of arms of the patrons and symbols of the apostles and saints. Centre: The arms of St John with dragons emanating from a goblet. Right: Both transepts are roofless and disused. The south wall of the south transept is still sumptuous with wonderful geometric Decorated style tracery in its window and with crockets and pinnacles.

The south porch has a highly ornate vaulted ceiling with many stone bosses. These two are unmissable. Left: A fox (bottom left) is running off with a chicken while the housewife (right) throws her distaff at him. This is a common scene in woodwork but not so much in stone, and certainly not in East Anglia. Right: Some unfortunate is having his ass thoroughly flogged by two monstrous apes. Nothing is left to the imagination.

Left: Looking towards the south arcade, showing the very fine and unusual clerestory with cinquefoil openings interspersed with more conventional small arches. Note the large and expensive-looking Perpendicular style aisle windows. Centre: The chancel somehow has a less exuberant, almost austere, appearance with an east window that is very much the poor relation of the nave and even of the derelict transepts. In mediaeval times, the rector would have been responsible for its upkeep and doubtless he was less able - or less willing - to finance lavish refurbishment. Right: The fifteenth century Seven Sacraments font, an East Anglian speciality.

The font’s panels have remained mercifully unmutilated. They show nice little scenes, looking rather like the journey through life of a single family. They are quite human figures, perhaps modelled on a family the carver knew (it’s not like me to be so fanciful - what am I thinking of?). Left: A group of children for confirmation Centre: Extreme Unction - the last rites. Note the standing figures carrying a book and holy oil. Right: The baptism. This is particularly nice as it shows the font on which this design is carved.

The spandrel carvings of the south aisle are the show-stoppers here. Left: A lion with an enormous (thigh?) bone. But what is that wrapped around his right side? Right: The best representation of a pipe and tabor player - a very common theme - that you will find in any church. Look at the drapes of the clothes. And the vestigial paint helps us to understand what a riot of colour our churches once were.

Left: St George fighting the dragon. This is far from the usual “dragon lying supine on the ground, knight skewers it with a lance” shtick. This looks like a hand-to-claw close quarters battle. Unusually too, we see the Princess (facing us) whom the gallant George is rescuing. George himself has his back to us on the Princess’s right as we look at it. His sword is still in his scabbard which looks like a bit of an oversight. Right: A lady playing a viol.

There are a number of poppy heads here. As is usual, it is a little bit difficult to discern how much is original. I think most is but you can see particularly clearly that the head of the man (top right) was sliced off by the iconoclasts and subsequently replaced. It could be a fox’s head.Mediaeval carpenters liked to use Mr Cunning for satirical purposes. They are a curiously disjointed group. and they do not all look to be of the same age, by any means

The north side of the south aisle (Confusing all this compass point stuff, isn’t it? But I can’t think of anything more helpful) has these slightly smaller and less elaborate spandrel carvings. It really is frustrating how difficult it is to work out what even undamaged sculptures are showing now the paint has gone or been scrubbed off by Victorian vandals posing as modernisers. Left: The figure is clutching something to his left ear. But what? Is it a variation on the “toothache” theme? Ear ache? Centre and Right: Both of these women seem to be possibly playing a psaltery - a triangular shaped stringed instrument. But surely it is more likely that one of them is supposed to be playing something else? Any ideas?

Left: Well someone is touching someone’s bum here! I don’t think it can physiologically be his own but my friend, Bonnie, disagrees. It’s a plump old bottom with testicles and short fat little legs. Up near the right hand side of the woman’s face is what looks like the head of a creature of some kind. A cat? Centre: This looks like another bum-exhibitionist. The gentleman who pointed this out to me speculated that it was an insulting gesture by the masonn towards the churchman or bishop who hadn’t paid him enough. This “explanation” for such gestures is found throughout the land. Unfortunately, it is total - if entertaining - tosh. The Church did not build churches: patrons and, later, parishes did. Cathedrals and Bishops - usually posited as candidates - most certainly did not. And the masons were paid by the day and usually by the contractor. Right: Who is this? Possibly the contractor mason? I believe many of the unidentified heads in our parish churches were actually of stonemasons rather than the popular “local worthy” theory. This one, though looks much too distinguished so more likely to be a patron. Or even a local worthy!

Left: This Queen’s head can be seen above the bum patting figure (see picture directly above) She is nearly hidden, somewhat like a royal spy! And where is her King? This is not some whimsical carving of an imaginary figure, is it? The most likely candidate is the formidable Phillippa of Hainault (1313-69) Belgian wife of the long-reigning Edward III. She was well-loved by the people and an adviser and sometime regent to her husband. Right: Misericord showing the arms of the Grocer’s Company on the right (cloves with a chevron) and a merchant’s mark. All of the six misericords (all the others are plain) have the initials “JG”, thought to be those of John Greneway, a merchant of Cley and Wiveton, whose mark also appears in Wiveton Church.. They were originally on the chancel side of the long-removed screen facing the east. They are then an example of church patrons gradually insinuating themselves into the sacred space in return for their largesse. The stalls are believed to be early fifteenth century so it is likely that “JG” had these marks added subsequently, the Grocer’s Company arms not having been granted until 1532. This shows how wealth and patronage in England had swung away from the landed gentry to the tradesmen and merchants.

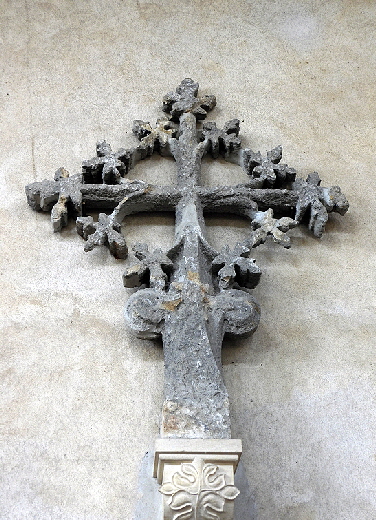

Left: Looking along the north aisle. This would have been a prime candidate for housing aristocratic funerary monuments, yet curiously there are none in this church despite its grandeur, something not remarked upon in the excellent Church Guide. That suggests to me - and I haven’t the inclination to research the issue - that Cley was of secondary importance to its patrons; as we know it certainly was for Sir John de Vaux and his predecessors who had holdings in rich Boston in Lincolnshire and other places besides. Centre: This cross, now mounted on a wall, would have originally adorned the outside of the church. According to the Church Guide it was removed “for reasons of safety”. One supposes it was seen as too precariously positioned. Right: Empty niches - or more accurately here, removed niches are less common in the naves or churches. I surmise this was once a statue of St Margaret to which the church is decorated. Paint is still visible, again hinting at the riot of colour that characterised mediaeval church interiors.

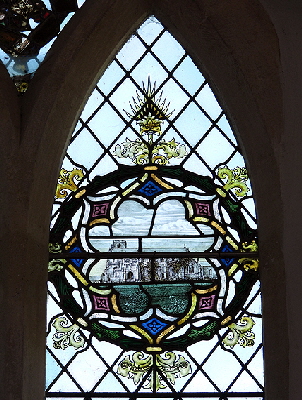

Left: Mediaeval stained glass to the east of the south door shows eight female martyrs. Right: In the otherwise clear west window is this beautiful image of the so-called “Cley Sparrow” - a white crowned sparrow from America which stayed in a local back garden for 10 weeks in January 2008, only a fourth appearance of this species recorded in Britain. A collection amongst the twitcher community raised £6000 which was used to commission local artist Richard Millington to design this commemorative window.

Left: One of the fine and very rare cinquefoil clerestory windows of the fifteenth century. Right: The equally fine “battlements” above the porch. Note the course of tiny cornice carvings.

Left: The ornate upper level - the “Parvise Room” - of the south porch. The room would have probably been used for a priest’s accommodation, storage and as a schoolroom over the centuries. The figure of St Margaret is of 1987. Right: The sourth transept showing its elaborate windows and decoration.

Left: An easily-missed little treasure is this drainpipe sculpture showing a lion wearing a mediaeval headdress. It is the pipework that dates from 1901, not the sculpture! Centre: Also easily-missed on the gable of the west end is that perennial favourite of East Anglian stonemasons - the wodewose. He doesn’t have his club poor chap. Hope there are no lions in the vicinity. Oh God, there’s one to the left! Right: A modern stained glass panel has an image of the church.

Faces of Cley.(All Photos Bonnie Herrick) Left: King Henry IV on the entrance to the porch. Other Three Pictures: We can’t of course, identify these men. They are possibly merchants but I think there is a good chance that one or more are stonemasons .The “local worthies” theory that is believed by so many may well in many cases be true. But it is strange how we assume that the stonemasons themselves did not bother to leave their faces for posterity. The hats here are rarely seen in any other context, but some contemporary pictures of building sites often show tall-ish, fez-like hats like these and I have not seen them in any other manuscript context.

Left: The north side. Right: The sadly destroyed north transept and the rather appalling “making good” work behind it. Ugh.

My church-visiting companion, Bonnie Herrick has a yen for churchyard monuments that I don’t have. And her love of skulls on monuments is probably a “mental ‘elf” issue (for which, in a just England she should be receiving disability benefits) but I believe it is untreatable. But even I was taken with the array of macabre sculptures in Cley churchyard. I particularly love the cadaverous crowned king (top left). Yes, we all go the same way, don’t we? It is understandable that church monuments vary in materials and fashion from location to location but no less fascinating is the local attitudes to death. Here in Cley they seem to have been gleefully determined to make the world aware that their loved ones are mouldering away underground. I doubt that fashion will ever return! Look for a coffin, a crossed shovel and pick and an hourglass. Right: I nearly missed out this picture of an angel boss within the south porch. What did the masons think this is - a church?