Clipsham

Clipsham, Rutland

Rutland is England’s smallest county but in its parish churches it punches way above its weight. To some, the choice of Clipsham as a subject may seem strange. There is a single reason for visiting - an extraordinary window at the east end of the north aisle, the like of which you won’t see in the proverbial month of Sundays. I can find time to write up only about a third of the churches I visit and there are many others that “deserve” my treatment more than Clipsham. But I like to write about those underdog churches that the authors of those big colourful coffee table books wouldn’t go near. If you are only interested in Simon Jenkins’s 1000 Best then Clipsham is not for you. If you love what is quirky and rare, then it is.

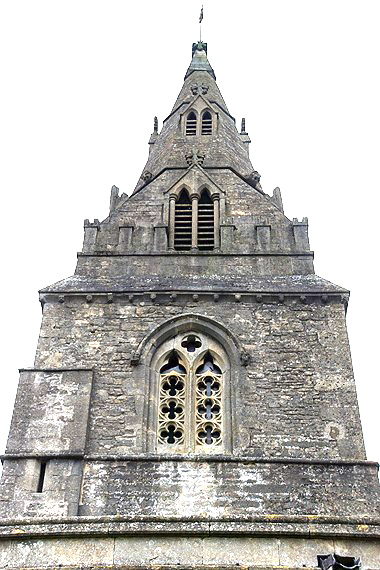

It is an awkward-looking building. One is immediately struck by the somewhat overpowering broach tower - using an architectural device that turns the square plan of a tower into a spire with an octagonal plan. There are so many of these in Rutland - see, for example Ryhall or Ketton that I have nicknamed them “Rutland Bruisers” and oversized seems to be one of their defining characteristics. But Clipsham’s has all of the bulk of the genre but none of the elegance. Instead of a smooth progression from base to apex, it has four distinct stages, Bizarrely, the masons reversed the broach device for the top stage, turning it into a square plan! I have not seen this

done anywhere else. Its lowest section has a curious course of weird little crenellated decorations boot. It is a peculiar composition all round as if it were attempted by a team of masons familiar with the concept but vague about the detail.

The broach spire does, however, prepare us for the fact that the church is more ancient than the rather utilitarian south aisle and clerestory windows suggest. Indeed, the arcades of the two aisles present a fascinating study in the transition between Norman and early Gothic styles. Both aisles have rounded arches,. Those of the north side, however, have shorter columns with somewhat clumsy-looking cushion capitals, whereas those of the south have columns that are taller and with octagonal capitals which, because they match the profile of the columns themselves, look much more elegant. So it is a late Norman church at its core.

The west tower, however, was built in around AD1300. The present south aisle followed perhaps a couple of decades later and we can see this from the course of Decorated style ballflower decoration on its west end. The Norman/EE arcades, however, show us that there must have been aisles here in the first place, so it likely that this was an extension of the aisle rather than a new build. This pedigree is reinforced by the aisle’s east window which has Decorated style curvilinear tracery and a surround decorated with ballflower, both characteristic of the style. The chancel and the south porch appear also to be of this period. The clerestory will have been later, probably early fifteenth century. The stone, by the way, came from a quarry in Clipsham itself. Part of the Limestone Belt, the quarry is still operational.

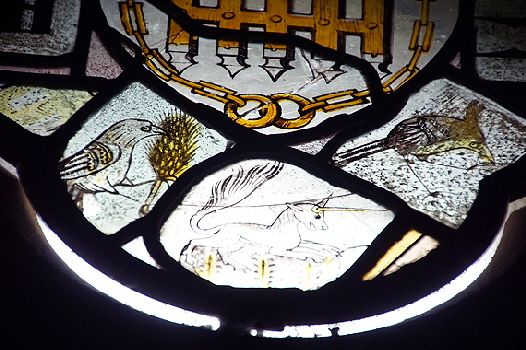

The treasure here is in the east end of the north aisle. Here is the remarkable window, glorious with brightly-coloured heraldry but with a host of birds painted into the intervening panes. I wondered for a long time what the rather comical bird figures me of and it the work of contemporary illustrator and satirist, Ralph Steadman, a number of whose books I own myself. It is said that the glass was brought here from nearby Pickworth Church. That church was destroyed after the battle of Losecoat Field in 1470 along with most of the village. But I think this is fanciful as I will show below.

Clipsham Church is a swine to photograph inside! The interior is really dark and the electric light, as you can see, are very harsh. These are the views to the east and to the west respectively. The most interesting thing to note is the difference between the two arcades. The north aisle has very slightly more complex arches seated on hefty columns and big square scalloped capitals. It is surely late Norman. The south aisle also has rounded arches so we know they are only a little later than those of the north.. The capitals are octagonal and have a narrow course of “nail head” decoration, an infallible pointer to Early English style. The columns are narrower. Thus we have a lesson in how late Norman architecture morphed into early gothic. We might go as far as to say that the two are early Transitional and late Transitional, which are not terms in common use!

Left: Looking across the two aisles from the south. Right: As if to retain the last vestiges of “Norman-ness”, the westernmost arch of the three bay north aisle has Norman moulded decoration.

Left: A Norman capital of the north aisle. Right: A capital of the South Aisle. It is octagonal. not square, and has a course of nail head decoration typical of Early English style but supporting a round arch.

Left: The west tower is a major curiosity. It has a broach spire: that is, it utilises architectural trickery to place an octagonal cross-section spire onto a square tower. They are not unusual in Rutland and South Lincolnshire but this was built in AD1300 - later than most - and is rather stumpier than most. However, there is much more that is unusual about it than that. The spire is in four distinct segments rather than being a uninterrupted progression. Then - I think uniquely - it has a square cap sitting on the topmost octagonal section! A the base of the lowest section is has a sequence of miniature turrets with little crenellations. Again, this is probably unique. The belfry windows have two lights with cusped trefoil heads. Above that a quatrefoil head is cut straight through the stone. The pretty inserts are later. Centre: The east window of the south aisle introduces us to yet another era of architectural development: the Decorated style. The tracery has evolved from the simple form of the bell openings into tracery made of individual carved pieces held together by iron staples and mortar. Around the window is a course of ballflower decoration, the archetypal Decorated style ornamentation. As the south arcade was in an early thirteenth century style, we can easily deduce that this window was inserted when the aisle was widened in the first half of the fourteenth century. Right: Looking through the south door, through the two arcades to the north door beyond.

Left: Another picture of the south side of the tower. The purpose of this picture, however, is to show the ballflower decorative course in the cornice of the south aisle. This shows that not only was the aisle widened (see its east window above) but also extended to the east to embrace the tower. Centre: Through the tower arch to the west wall beyond. To left and right are arches to the western extensions to the aisles. Right: The font. Plain fonts are not always easy to date but the row of decoration here suggests to me that it was contemporary with the late twelfth century north aisle

Left: Looking along the north aisle. Through the arch is the organ that virtually fills the aisle at this point. You have to shimmy past the organ to get into the tiny space at the east end where the lovely east window is situated. if you ain’t slim enough you can just about get a glimpse from the altar area. Right: Courses of carved faces with couple of devils in evidence as well as a rather nicely-carved be-whimpled lady.

Left: This is the only feasible angle to capture the whole window. Centre: The central coat of arms has the badge of William Catesby of Ashby St Ledgers, Northants in the top left and bottom right quarters. the other two quarters have ermine devices almost certainly of his wife, Margaret la Zouche. I don’t know whose are the diagonal bars. Upper left from this are the arms of Thomas Neville. another great family. But which Thomas? Probably Thomas Neville of Pickhill. The black and white shield upper right belongs to a branch of the Browne family. William Browne, a very rich wool merchant, was a VIP in nearby Stamford where he founded Browne’s Hospital. His married Margery Stokke (or Stock) of Warmington, Northants and incorporated a stork into his arms - a play on the name Stock. This image does not look much like the stork in his arms in Stamford but it does seem a coincidence to see it here right next to Browne arms. Surrounding it all, of course, is the wonderful bird glass, of which much more anon. Right: The royal arms of England of 1399-1603 : from the usurper Henry IV to the start of the Stuart dynasty with James I. The insignia of the Order of the Garter surrounds it.

Left: The royal arms of the Stuarts, showing the insignia of Scotland and Ireland whilst the mediaeval arms occupy two quarters, thus maintaining via the fleurs de lys emblems the bizarre pretence that England still had claims to the throne of France. Quite clearly these arms, at least, could not have come from the long-ruined church of Pickworth! Right: The arms of the town of Stamford, eleven miles from Clipsham and five miles from Pickworth.

Left: The red rose badge of the House of Lancaster. Contrary to our modern understanding it seems that it was not used as an emblem of the Lancastrians during the Wars of the Roses - and they were not called the Wars of the Roses then either! It is very clear that tis particular emblem was damaged before being reassembled here. Right; The portcullis emblem of the Beaufort family. It was much used by Henry VII and also by his mother. Margaret Beaufort, who had a palace at Collyweston just outside Stamford.

Left: The arms of Thomas Neville. There was more than one Thomas, but it is believed that this one was from Pickill, Yorks. Centre: Bird on the curve of the arched window. Right : Er…a bird!

Lots more Birds…and a Unicorn!

Left: A bird in the curve of the mediaeval bird window. Centre and Right: The Victorian version of the bird window in the west end of the north aisle. The artist has clearly got all of his insipiration from the mediaeval window but has chosen to arrange the birds in horizontal courses.

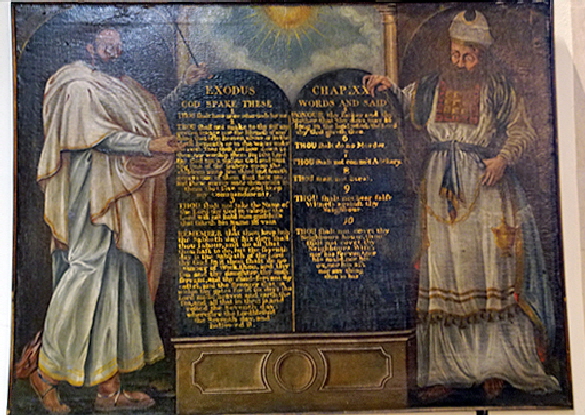

Left: I can’t get the measure of this pretty Victorian glass of 1858 with flowers. The name “Emmanuelle” appears all over it. Right: On a board in the north aisle a pair of tubby old prophets present the 10 Commandments.

A varety of heads. The one second right looks decidedly Elve-ish!

Left: The church from the north east. Right: One of the strange grotesques on the tower

Where did the Glass come from?

When you see stained glass in a church you don’t normally ask that question, do you? You assume the glass is where it always was. Yet at Clipsham there is a universal assumption that this was not the case. This applies to the heraldic sections which have fairly obviously been incorporated into glass originally entirely comprised of bird paintings. That this was the case is probably why the heraldic glass is assumed to have come from elsewhere. Moreover, it has been stated over and over again that it came from Pickworth in Rutland (not to be confused with Pickworth near Grantham). And when I try to find out who said this, all I find is that a man called “Blore” said so! It turns out this is Thomas Blore, author of the “History and Antiquities of Rutland”

He lived from 1754-1811 and is described in Wikipedia as a “diligent English topographer”. So that’s pretty definitive then! This is a slight variation on the “If Pevsner says it’s Sunday, it’s Sunday” syndrome. It seems likely that his thinking was that if the glass came from anywhere it would have been from a church that had been demolished. And Pickworth is literally just down the road from Clipsham and its church has been demolished, probably after the Battle of Losecoat Field - see below.

I have been unable to track down his precise text on this matter. “The Victorian History of Rutland” says Blore supposed this as the glass “has the ams of several former owners of that parish (ie Pickworth). That particular document itself has comprehensive accounts of the ownership of all the Rutland parishes and I can find no association whatsoever between the families represented in Clipsham and those at Pickworth! So this acceptance of Lore’s statement was a but odd.

What families are they then?

Thomas Neville. We know of two Thomas Nevilles from this period. One was the brother of Richard Neville, the Kingmaker. He was killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460. Another Thomas Neville lived from 1405-82. Although a Neville by name, he does not seem to have been closely related to the Earls of Warwick or, more specifically, to Richard Neville, the Kingmaker, who precipitated the battle of Losecoat Field in the first place. That Thomas was born and died in Rollaston in Nottinghamshire and was a relatively minor public servant.. He was also associated with Pickhill in Yorkshire. This is why sources talk of him as “Thomas Neville of Pykhale (or Pykale)” without (lazily?) looking into where this actually was. Not Rutland, for sure. There is no known association between him and Pickworth.

The Catesby family. Like the Nevilles, this is one of the most important families in English history. Family arms are invariably adapted to individuals, often incorporating elements of the arms of the spouse. The Catesby arms here incorporate quarters of ermine. That suggests these were the arms of William Catesby (1450-1485). He married Margaret de la Zouche and many of their coats of arms incorporated just that device. If I am right, then we are talking about someone who was to be a very important man indeed. In the short reign of Richard III he was immortalised in the rhyme of the time: “The Cat, the Rat and Lovell, our dog rule England under the Hog”. The Rat was Sir Richard Ratcliffe. Lovell our Dog was Viscount Lovell. And the Cat was William Catesby! Catesby, then, was one of the three counsellors seen to be governing the country. The significance of the date of his death - 1485 - is that after the Battle of Bosworth Field he was captured and handed over to the people of Leicester who promptly executed him! A later Catesby - Robert- was one of the instigators of the Gunpowder Plot more than a century later.

The Catesbys were mainly a Northamptonshire family. Significantly, William and his wife, Elizabeth ,are buried in the church of Ashby St Ledger (where many plausibly believe the Gunpowder Plot was hatched). Would they be commemorated at Pickworth? The only minor association I can find is that Elizabeth’s father was the Baron of Harringworth. twelve miles away from Pickworth. But that’s tenuous, isn’t it?

- The Browne family. This is the clearest of all the arms here, but by the same token there is no clue as to which member of the house this refers to. Again, I can find no links between the Browne family and Pickworth. The Brownes, however, were famous in nearby Stamford where William Browne, a fabulously rich wool merchant, founded “Browne’s Hospital. His own arms were totally different but the arms we see at Clipsham may, of course, reflect later generations of the family.

There is nothing here at all to suggest any of these arms originated in the tiny village, let alone all three! And it simply beggars belief that two such illustrious families were there.

Let’s continue. The most easily distinguishable arms in the Clipsham window is that of the town of Stamford, five miles away. Stamford was a Yorkist stronghold and was sacked by the Lancastrians in 1461. There are also two sets of royal arms. One set of arms is of 1399-1603!. The other set of of the Arms of England is Stuart! The latter could not possibly have come from long-demolished Pickworth Church.

Finally, and of no less interest, are the less obvious “graphics”. Firstly, the red rose of Lancaster. Firstly, historians believe that the red rose was not used as a symbol of the House of Lancaster during the Wars of the Roses. And at the time they were not known as The Wars of the Roses! Then there is the portcullis. That too was a Lancastrian symbol, although it came to have a wider application. But it was largely associated with John of Gaunt - a Lancastrian - and Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII.

Put all of this together and what do we have? Firstly, it is inconceivable that this hotchpotch of designs (including the Stuart arms and a Lancastrian rose forsooth!) were ever a coherent set. Secondly, it is even more inconceivable that they all - or probably any of them - came from Pickworth. Blore’s analysis was simply fanciful. His assertions would have been near-unchallengable at the time. There is much less excuse nowadays when we have the resources of the Internet at our disposal.

So where did they come from? I haven’t a clue. Almost certainly from a variety of sources, I would say. One thing we night like to think about is that Stamford, five miles away, is renowned for its five churches. But in mediaeval times it had fourteen churches, as well as a castle that would have had a chapel. Could some of the panes have come from those, especially the arms of Stamford and quite possibly those of the Brownes? But where on earth could the arms of Catesby and Neville have come from?

It’s all a mystery but I can’r see anything to support Blore’s assertion of two centuries ago. Unless you know anything different?

Footnote - The Battle of Losecoat Field

The battle ensued from a rebellion against King Edward IV by Sir Robert Welles, a Lancastrian, incited by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick the so-called “Kingmaker”. Warwick had lost influence after Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, and his supporters had defeated Edward at the Battle of Edgcote (Northamptonshire) in 1469. Edward had been captured and many of his supporters slain. Warwick seems to have thought he could rule using Edward as his puppet. Edward, however, regained power through the support of his brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, later Richard III. Thwarted, Neville incited Welles to raise rebellion in Lincolnshire. Edward heard that a large force was advancing on Stamford. Neville marched north with a hard-bitten army of experienced soldiers to join with Welles’s army at Leicester. Edward, however, held Welles’s father as prisoner and threatened to execute him. Robert Welles fell back towards Stamford and was brought to battle near the Great North Road, close to Empingham in Rutland on 12 march 1470. Welles’s father was beheaded anyway in the no-mans-land between the two armies before the battle began. The rebels wee soundly defeated by Edward’s own battle-hardened troops. Welles was executed a year later. Neville fled to France. Stamford Castle was subsequently largely demolished during the short reign of Richard III.

The battlefield was close to an area of woodland now known as Bloody Oaks. Legend has it that many of the rebels were wearing the uniforms of Warwick or Edward’s brother, George Duke of Clarence. It is said that when they fled they threw away their incriminating clothes, hence the name “Losecoat Field”.

That is the legend. However, it is now widely disputed. In Old English ”hlose-cot” means Pigsty Cottage and its corruption Losecoat is known in other Rutland parishes. Whether or not you believe the legend, it is certainly a good story and still has local currency in the Stamford area.

Pickworth, from whose church the bird glass is said to have come, is close to the battlefield and has been described as having been destroyed. Certainly, there is no trace left of the village of that time and the present church dates from Victorian times.