Colsterworth

Colsterworth, Lincolnshire

As you whizz up the A1 going north you will see the Colsterworth/A151 exit surrounded by petrol stations, fast food outlets and one of England’s biggest truckstops. It’s a handy place for the motorist. You are unlikely to make the detour to the village of Colsterworth just half a mile away but if you are interested in churches or just have a sense of history you should make yourself an exception. The church is open from 9.00-4.00 every day at the time of writing (June 2022).

We British (I think I can speak for my Celtic cousins as well) are exceedingly proud at producing the world’s most renowned poet and playwright. Somehow, though, we don’t seem to equally treasure Sir Isaac Newton who first identified gravity and the laws of motion. Of course, we might argue that Shakespeare was unique whereas Isaac - and all scientists - are just the the first to discover something. But Sir Isaac Newton? He discovered fundamental stuff. Like Einstein but four centuries before.

Anyway, young Isaac was born and lived at nearby Woolsthorpe Manor and was educated at Grantham Grammar School. And he was christened in Colsterworth Church font. I understand that the foreign visitor would prefer Shakespeare, Burns and Beatrix Potter (what, you haven’t seen how many Japanese and American people flood the Lake District as Potter Pilgrims?) but we Brits should be more cognisant of one of our foremost geniuses.

If you just don’t get turned on by famous associations, however, Colsterworth Church - unheralded by Jenkins, Harris and Co - has plenty more to offer.

For a start, it has three of the best obscene carvings - two gargoyles and a label stop - you are ever likely to see on one parish church. Bring your binoculars! Then it has that Newton font: Gothic stem and a Victorian faux-Norman bowl.

The church itself is ancient. Herringbone masonry in the north aisle (originally the nave wall) proclaims eleventh century. The church itself believes there was a pre-Conquest building and even goes as far as to show a model of it as they suppose it to have been in AD1000: a simple single-celled prayer hall with round-headed windows. Are they right? The Domesday Survey of 1086 does not mention a church but it is known that many churches were not listed in that famous document. Interestingly, by the way, the vil is recorded as being owned by a “thegn of the queen”. This is extremely interesting. Matilda of Flanders, William’s queen, had died in 1083. Indeed, William himself died in 1087. This shows that the survey here was conducted at least three years before the book itself was competed in 1086. More about that in my footnote. In the meantime, those indefatigable chroniclers of all things Anglo-Saxon, Taylor & Taylor, do believe the nave walls to be be pre-Conquest, basing that upon walls only 1’10” in thickness: Norman walls were very rarely less than 2’6”. So I think we have to assume the church’s own case to be proven. There is also a fragment of an Anglo-Saxon cross shaft within the church but, of course, we do not know where this came from, although it might have been on the site prior to the first church. One account I have seen goes as far as to say that “some experts” have suggested that the original building may have been built not long after the departure of the Romans but we have to place this in the box marked “fanciful speculation”, I think.

Also certain is that a Norman north arcade was cut through the north wall to form an aisle of two bays in about 1150. A further western bay was added later in the Norman era and it was a horrible bodged job. Pevsner speculates that it may have been the intention to add a tower at this point, but that clearly did not happen. The south door is in Early English style (so around 1200-1280) so there must have been, as the church suggests, a south aisle added during this period, although I personally think that the mooted AD1200 is mere speculation. The arcade arches are clearly not in keeping with this dating, however, and the arcade was rebuilt a century later. In 1305 the tower was added by the mason Thomas de Somersby who, remarkably and obligingly, left us an inscription at its base. Presumably the south aisle rebuilding coincided with this addition. How odd, though, that the south arcade was rebuilt but the older northern one was not? The clerestory was added probably early in the fifteenth century along with the top section of the tower. We don’t know the nature of the original chancel because it was completely rebuilt in 1870, featuring faux Early English style side windows and a faux Decorated style reticulated window.. It is not, I have to say, a handsome space.

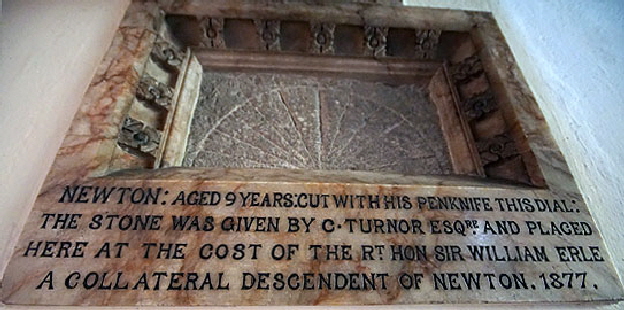

So, quite a complex and not altogether clear history. Other things of note are some fine “angel” carvings in the nave ceiling, including some nice musicians. In the north chapel a sundial carved by Isaac Newton is preserved. What a treasure!

Finally, I am indebted to a former churchwarden who, on my fourth visit to the church (!) proved my oft-stated view that a real local enthusiast will always be able to point out something you could not otherwise know about. In this case he pointed out no fewer than four apotropaic marks (designed to confuse and trap witches) shallowly inscribed. See my footnote for the significance of this.

Have I convinced you to make a short detour from the A1? I hope so. Visit the church and celebrate one of Britain’s innumerable contributions to scientific discovery.

There are quite a few obscene gargoyles in this part of the East Midlands but two is a bit of a luxury and these two are particularly spectacular. There is something particularly lascivious about the face of this exhibitionist (left). While the mooning gargoyle (right) treats us to a view of the man’s face as well as his testicles, His head seems to be partly covered, which is a bit odd. Also odd is that the face looks human but the body does not - well, apart from the testicles!

Left: Looking towards the east and the Victorian chancel. The age difference between the Norman north arcade and the Decorated style north arcade could not be more obvious. Obvious too is the horrible job the masons made of blending the additional western bay on the north side into what was already there. See the extreme left of this picture. Right: The north arcade from the east. The eleventh century herringbone masonry is very obvious and you can also see that the wall - the original north wall of the nave - is indeed very thin and characteristic of pre- rather than post-Conquest architecture.

Left: The view to the west. You can see very clearly the pre-clerestory roofline. But something’s not quite right here. Why is the west window of the tower so badly out of alignment with the tower arch? Well, the answer was thought to be that the tower was originally separate from the body of the church and that the aisles were not extended to meet it until towards the end of the fourteenth century. By implication, then, de Somersby did not need to bother about the position of the windows relative to the rest of the church. Does that ring true? Not to me. The whole concept bamboozles me because I can see no sign that the south arcade has been extended. What is more, it is the tower arch itself that seems to be off-centre with a bias towards the south. That suggests that this was the cause of the misalignment and it is possible that there was some structural reason for it. I am sticking my neck out here but I do not believe the tower was originally separate. It would be very unusual and where separate towers do exist they are rarely to the west of the church. I don’t mind if someone wants to contradict me. Centre: The the entrance to the rood loft. Pevsner reported that there is nail head decoration to the upper doorway, indicating Early English provenance and therefore one of the oldest rood stairs in the country. Right: The font. It is a mystery too. The bowl is nineteenth century, its blind arcading decoration imitating Norman style. But the stem is fifteenth century with little ogee-arched niches filled with strangely weathered sculptures, including the easily identifiable agnus dei. So, sadly, Newton was not baptised in this bowl but in a bowl that previously sat on this stem!!

Left: Another side of the font. Centre: This is clearly authentic Norman carving on the font stem. If you look at it closely the stem you can see that it was originally much taller - it has been cut off at the knees, as it were. The rest of the stem is indisputably post-Norman and pre-Victorian, so this is all deeply weird. The only rational explanation is that this section was originally part of a Norman font bowl: that the stem itself was a replacement for a Norman original. After the Commonwealth many of our parishes fell out of love with their Norman fonts and often not-very-Biblical decorations and consigned them to the churchyard or gave them to farmers for feeding troughs - I’m not joking. I am guessing this font suffered the same fate and when it was brought back inside the church the bowl was badly damaged and had to be replaced. I think this section was recovered from that Norman bowl - it is very characteristic of a Norman font bowl - and incorporated into the stem which itself was not unscathed. And if you look carefully at this picture you can see how it has been mortared in and somehow made to cover two of the six sides in a most DIY way. Are you unconvinced? Alternative explanations would be very welcome! Right: Agnus Dei on the font stem. Look closely (again!) and see you can see it has been considerably weathered. Why? Because it was chucked out of the church at some point and left in the open - see the previous picture.

These four roof “angels” are unusual. Why? Well, for a start they manifestly are not angels. Each of them sports a padded headdress that would have been worn by an upper class woman of maybe 1420-30. Three of these women are playing musical instruments - respectively pipes, sackbut (?) and zither and I am struggling to think of a female band in any other church I have visited. If they were angels they would not have been so unusual. These figures probably tell us the approximate date of the clerestory. Are they unique? The figure with the sackbut has inexplicably had her left arm and shoulder either removed or left off. This leaves behind what looks like a St George’s cross but the right bar of that cross actually wraps around part of the instrument. It looks like it represents the cross of St George hanging from the instrument when it is held horizontally - such as you see when the heralds blow their trumpets in Westminster Abbey on royal occasions. I always think that zither looks a bit like a washboard. Was this a mediaeval skiffle band?

Left: The Victorian chancel. We know little of what was here before. Fowler, the architect chose to use faux-Early English lancet windows to the south side and an east window in reticulated Decorated style. The whole thing looks a lot darker than it does in this enhanced picture and the reddish stone Fowler used was perhaps not the best idea. Still it is inoffensive enough. Right: The north arcade from inside the aisle. Architecturally it is a bit of a mess with three different styles of capital, a slightly higher western arch and its incompetent jointing with the neighbouring one. One of the reasons for this undoubtedly is the uneven ground upon which the church is built.

Left: The plaque speaks for itself. Think of this as the equivalent of finding some of Shakespeare’s schoolboy poetry. This boy was carving sundials with his penknife at the age of nine! That would be a penknife actually used for stripping feathers to form a pen, by the way, not a Swiss Army knife. This is located within the north chapel behind the organ. Don’t be fooled by this picture which was taken with a 20mm lens. It is a very tight spot! Extraordinarily, Pevsner thought it was not worth mentioning. Right: One of four “witches’ marks” on this church and you wouldn’t spot them unless they were pointed out to you - as they were to me by the churchwarden. This slab is below one of the north aisle windows. It is obviously carved - crudely - with compasses. These “daisy wheels” are easily carved with compasses and, as you can see here, it does not require an accomplished mason. Such marks are very widespread and very ancient. Although we call them witches’ marks and although they were quite likely to be have been carved here with that specifically in mind, such marks were all-purpose “Defence against the Dark Arts” as Hogwarts School would have known it. Demons and witches hated circles and spirals . More about this in the footnote.

Left: This view of the north west corner of the church reveals the aesthetically unfortunate failure to properly blend the later westernmost bay of the north arcade with its neighbour. Note the lonely little Norman head and the water leaf capital. Right: The topmost stage of the west tower. This is in Perpendicular style and not, therefore, part of the 1305 build. Note the odd carved rectangular stones that seem to be half-decorative cornice, half-corbel. When you look at this picture you see the hefty bell stair on the left and the buttress on the right and begin to understand the thorny issue of alignment of windows. As a mason, do you place the window line in the dead centre of the whole face (as seems to be the case here) or in the centre of the space between these two raised sections? Did this calculation account for the non-alignment of the west window of the tower with the east window? Note the old “put holes” to the left and right of the bell opening, presumably the location of the mediaeval scaffolding. Some of these holes, at least, are inhabited by jackdaws who love to perch on the gargoyles and label stop carvings! “They ain’t afraid of no ghosts”!

The parapets, pinnacles and gargoyles of the north face of the tower.

Left and Centre: These two label stops on the Perpendicular style west window of the north aisle are most interesting and different in style from others on the church. Interestingly, and not immediately obviously, the left hand specimen is a mooning man, very much in the style of the Mooning Men Group of masons - see below. His face is visible between his legs. His appendages perch improbably below his anus. Right: A gargoyle with an armoured look - a bit like a stegosaurus!

Top Row and Lower Left: Three images of apotropaic marks found on the north, south and west sides of the west tower. They are shallowly carved, hard to spot and situated at a height out of reach without a ladder. They surely have been inscribed not by a mason and they clearly were not intended as mere “doodles”. The best for visibility is top left where a double circle encloses six “petals” in a classic “witches mark” configuration. Others are not so easy to discern but all are circular and do not appear to be identical. Right: The fourth of the gargoyles.

Portion of an Anglo-Saxon cross displayed in the south aisle.

Colsterworth and the Mooning Men Group

In my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men”, I included Colsterworth as an outside possibility as a church that was worked upon by that peripatetic “Mooning Men Group” of masons at the turn of the fifteenth century. When I rewrote the “book” in web format in 2022 as “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers”, I excluded it from the main body. Along with nearby Careby and Market Overton, I concluded that on reflection the pointers to the MMG were too slight, confirmation bias being my perennial foe.

Of those three, Colsterworth is still the one where the best case can be made for the MMG. The principal pointer, of course, is that mooning man label stop (see main section) is very much in the style of the MMG but tantalisingly very slightly different by dint of the penis and testicles being visible externally. Nor is a label stop the usual place for this carving, but there is no cornice frieze - other than high up on the tower - on which it could have been be located. Its companion label stop carving on that north west window is also perfectly in keeping with many others within the MMG ouevre.

Another pointer to the MMG is that the church is just within MMG geographical territory and is less than four miles east of Buckminster Church which is very definitely one worked upon by the MMG. Indeed the Colsterworth label stop face with drilled holes for eyes is very similar in style to many carvings there.

A question I have addressed much more fully in the second edition of my work has been “what were they doing here?” rather than focusing exclusively on the carvings, and recognising that masons did not just turn up to do decorative work: they would be at a church primarily to build something. If the MMG was at Colsterworth, what were they doing?

Well, putting in that north west window obviously! Anything they were doing would be in the Perpendicular style as that window is. Other north aisle windows look to be Tudor or Victorian replacements. Was this window just a one-off job for a passing MMG mason - or one that was diverted from work at Buckminster? Did the MMG masons put in a series of windows on the north aisle of which this is the sole survivor>

The mooning gargoyle is something of a red herring, by the way. There are several others in the area

cand none can be attributed to the MMG. Putting in the embattlement, pinnacles and frieze of that top section of the tower would have been right up the MMG street. The frieze, however, is unlike any of their other work. Moreover they invariably placed their gargoyles at the cardinal points of the compass and not at the corners as here. It is certainly possible that they did install the Perpendicular style clerestory as this was very much MMG stock-in-trade. If so then it pre-dates the wooden ceiling (see above) that sports wooden carvings of women in headdresses looking twenty or thirty years too late. I can see no real reason to support the notion that the MMG built it.

On the whole, I incline to the view that one or more of the MMG - probably John Oakham and his sidekick Simon Cottesmore who were at Buckminster - turned up here and installed this single window, leaving the MMG’s trademark sculpture, and perhaps more north aisle windows since replaced.

Footnote - “Apotropaia”

As I observe in my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” narrative, apotropaia is a knee jerk and lazy response to the question of why our churches so often sport external, seemingly inexplicable, grotesque and humorous carving. Apotropaia, in short, is the notion that such drolleries deflect evil spirits . That such things are a perennial worldwide phenomenon is incontrovertible. Do you have a horseshoe on the outside of your house? Have you bought souvenir ceramics in Southern Europe with a great big eye painted on the side. Yes, apotropaia is a thing.

But it did not inform our external church carvings, of that I am certain. If this were so, why do all churches not have them? Were there some churches that were not concerned with evil spirits whereas other were apparently obsessed? Why would a church like nearby Ryhall in Rutland - to choose one from many possible examples - have hundreds of apotropaic carvings? How much deflection did evil spirits need, for heaven’s sake? Indeed, if my work on the MMG proves anything it is that the carvings that they produced were almost certainly mason-driven. Other studies suggest that mediaeval “drolleries” and “baebwyns” (baboons) were treasured for their entertainment value, not for their supposed protective qualities.

My killer argument is a simple one: if this ubiquitous carving was designed for such purposes, why do we have to use the dumb-ass, pretentious pseudo-anthropological word “apotropaia” in the absence of a single surviving word from mediaeval documents or a single reference to this supposed phenomenon? In my view, it is twaddle. Quite how we ended up with so much of this type of carving is open to question as must be the case for all artisanal folk carving of this kind. Artistic traditions, come and go and mutate. We cannot even agree on a common meaning for the ubiquitous green man carvings on our churches.

But here at Colsterworth, we have another argument. When the top portion of the tower was built in probably the early fifteenth century, four gargoyles were apparently regarded as sufficient apotropaia for one church, if you believe they had that function. Yet a century or two later, it seems, people - ordinary and frightened people in all probability - drew their own apotropaic marks. On the same tower. And those markings are mysterious and subtle. We might not understand the thinking of those that took the trouble to draw them but they surely did. And they did not believe, it seems, that a handful of grotesque carvings fitted the bill at all. Of course they didn’t

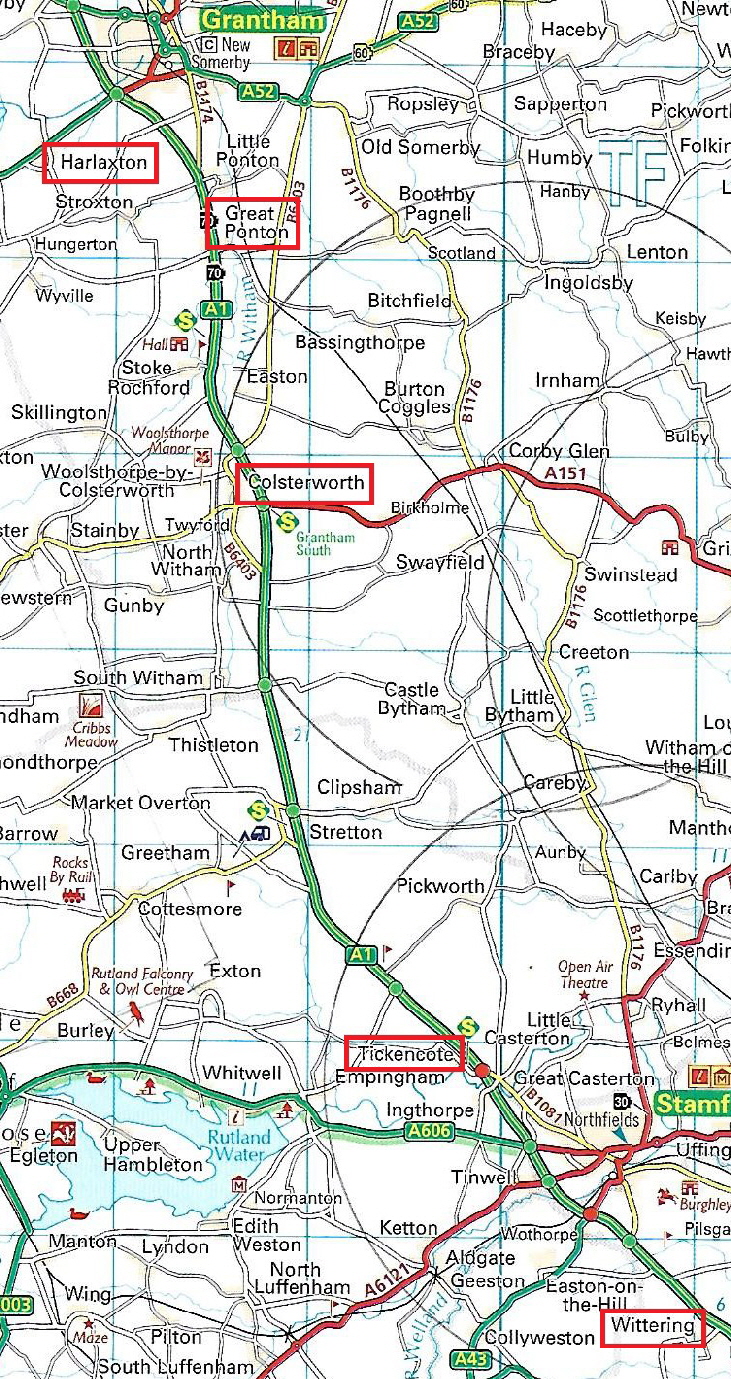

The A1 Trail

If you are a dedicated church visitor, are you sometimes thinking it might be nice to break your journey with a church visit? Not too far from the main road because you are in a hurry. But do you look wistfully at the church steeples as you rush by? Well this is you own little church trail for when you are in the Stamford and Grantham areas. There are five churches here. And they are all a stone’s throw from the A1 in Lincolnshire, Rutland or Cambridgeshire; four on the west side and one on the east.

As you hurtle north, head off for Wittering just south of Stamford. The church with maybe the noblest Anglo-Saxon chancel arch in England is about a quarter of a mile from the A1. To do it quickly you will need the postcode for your satnav because this is a substantial village attached to an RAF base. PE9 6DZ. One snag is that it is a keyholder church. Check its website for the latest collection place - usually a shop. I have never actually had a problem collecting it within normal business hours. Parking easy. Shops and pubs should you need them.

Now head seven miles up the A1 to the real gem at Tickencote with the undisputed British Champion Norman chancel arch and a gorgeous Norman chancel. If you visit one of these churches, make it this one, The church is literally a hundred metres off the A1. Parking no problem. NB No other facilities in this hamlet.

You are on a roll now, right? So head north for about ten more miles and turn off at the junction with the A151 at Colsterworth. You are going to have to go half a mile this time (oh no!). Drive Into the village (straight road) and take a right turn at the red post box. You can’t miss the church on your left after a couple of hundred metres. Park in the road right outside. This church has Anglo-Saxon roots, deliciously obscene gargoyles and the font in which Sir Isaac Newton was christened. Pub opposite if you need a pint and a pee. A Co-Op Local (a good one) a further couple of hundred yards along the road to the right.

Your next stop, should you choose to continue your mission, is Great Ponton about five miles further north. This is a locked church. To be honest, the interior is nothing to write home about so I wouldn’t arrange for it to be opened unless you have a particular interest. But the gargoyles on the west tower are the best I have ever seen and there are other wonderful sculptures lower down on the tower. There is a car park and the church is almost literally alongside the A1. Your quickest diversion perhaps. No other facilities that I know of.

Then head about another four miles north. I’m cheating a bit because I think Harlaxton Church might be as much as a mile and a half away from the A1. Forgive me! But it’s a straight road to a church with its own car park. It has great carvings and was worked on by “John Oakham” of the Mooning Men Group of masons - see above. A very pretty church with a lot to see and a very intriguing font showing Henry IV and some interesting iconography. There are two good pubs in the village.

So there you go. Five worthwhile visits to churches of genuine merit very close to the A1. What’s not to like? Just allow yourself a couple of hours extra time and gorge yourself!

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future?