Lowick

Lowick

If you ever wanted to know what a fifteenth century church looked like when it was built then you could not do much better than to visit Lowick. It was almost all built by the Greene family before 1420. The tower - a magnificent landmark with a “lantern” followed in about 1470. There are one or two clues to an slightly earlier church but this is to all intents and purposes an unrebuilt Perpendicular style church. This gives it a harmony in its geometry and its windows. Yet one might argue that its virtues are somewhat offset by its bland exterior: bland, that is, apart from that tower!

It stands slightly detached from the village and perhaps that is fitting for a building that was all about patronage. It is disproportionately large compared to its community to the extent that it faces “closure”, its congregation sometimes dropping to two elderly worshippers in 2024.

The inside of the church is little more exciting than the exterior: its virtues, again, are in the integrity of the building as a fifteenth century work of architecture. Do not look here for much in the way of adornment or droll art. As we shall see, however, the church has priceless treasures of mediaeval stained glass and glorious funerary monuments.

The glass, however, pre-dates the Greene church and is early fourteenth century.

The most celebrated monument is to Sir Ralph Green (d.1417) and his wife - surely one of the finest in the country. There are seven monuments here, only three of which are mediaeval but all of which are high quality.

If one considers that the glass pre-dated it and that all but one of the monuments we so admire post-dated its building it is not unfair to say that the Greens commissioned a remarkably dull church! Don’t look here for anything architecturally stunning or for any entertaining sculpture. It is in essence a huge prayer barn housing the Greens’ family monuments. As the distinguished Gabriel Byng suggested, the glory of the Perpendicular style was seen to great advantage in cathedrals and priories but in the average parish church, as here in Lowick, it was often humdrum. See the footnote for much more on this topic and my discussion on whether Lollard beliefs influenced the structure So, it is to glass and monuments we must look and let’s not waste time trying too hard to find architectural virtuosity here.

The early fourteenth glass appears in four Perpendicular style windows. They fit so well that the Church surely has it right when they say that the “new” windows must have been customised to receive this older glass. The moulded transom below the actual windows are a Perpendicular style invention so I don’t think it could be a case of the whole window being recycled, tracery and all. They are “Tree of Jesse” windows designed to show the lineage of Christ back through the prophets and kings off Judaism - another thing enabled by Christianity’s (dubious?) adoption of the Jewish scripture. It’s all very strange when you think about it. Jews were widely despised and even persecuted in mediaeval England yet churches happily showed Christ’s supposed Jewish lineage. I know there will be scholarly studies that try to show there is no contradiction here but excuse this poor ignorant soul if he just doesn’t get it! Tree of Jesse windows are of a large piece and not done in “cycles” as this one is - the key is in the “tree” bit - so they must have been constituent parts of a much larger window in the previous church. This accounts for the rather odd incorporation of figures squeezed in at an angle inside the top lights. All the evidence of that previous church is that was it was no more than a hundred years older. The iconography here was not outmoded and the glass itself must have been extremely expensive. It is little wonder that the Greens chose to keep it albeit in this unorthodox manner. The church discusses the possibility that some other windows were destroyed at the time of the Civil War. Left: (All of this information courtesy of the Church’s own information boards) Kings Rehoboam (who he?), David with harp, Solomon and Asa. John the Baptist and a Bishop in the top lights. Right: Jacob. Isaiah, Elias and “Habbakuk”. Maybe St Stephen and an Apostle in the top lights. Note the orphaned wording at the bottom of the two right hand panes - more evidence that they came from a previous window.

Left: Daniel, Ezekiel, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. St Michael and a nun in the top lights. Right: Joseph, Zacharias, Micah and Simon de Drayton. Simon de Drayton was the benefactor of the previous church. Here, dressed as a Crusader, he holds a picture of the church. SS Margaret and Andrew in the top lights. You might ponder - or maybe it was obvious to you - that Jesus apparently had no women in his lineage. No wonder so many opponents of the ordination of women dip so freely into the OT for their arguments. Just sayin’.

Click Here for a gallery containing bigger pictures of these windows.

Left: Looking to the east. This church being all of an early fifteenth century piece, everything fits. The arcades are identical. Light floods through the clerestory windows. The aisles are a little narrow perhaps but that allows even more light to permeate into the nave. Take away that imposing royal arms over the chancel, however, and what have you got? A huge space with very little adornment: a rather antiseptic environment, grandly proportioned but somehow soulless. You might point to the stone parclose screen around the south chapel just visible to the right; but this was installed in 1850. We must pose an important proviso, however. Were these walls ever painted? There is no sign that they were but in so many churches they are only uncovered by accidental damage to the plaster. See my long footnote below for some discussion of all this. Centre: The north aisle, looking east where Bonnie Herrick is busy with her camera! The mediaeval glass is in the windows to the left. Right: The tower is architecturally the crowning glory of the church, built in 1470 by Henry Green who probably never lived to see it completed. It too, of course, is in the Perpendicular style but here we see the flamboyance of the octagonal lantern.

Left: The Tree of Jesse windows seen from the south aisle. Right: The view to the west end. The enormous tower arch and hefty west window all help to flood light into the church, which must have been seen as nirvana in the fifteenth century when the pursuit of more light was leading to all manner of lash-ups to older churches constructed when glass was so expensive.

The Ralph Green (d.1417) and Katherine Green Monument

This is by common consent, one of the finest of all English church monuments. Ralph was the son of Sir Henry Green who was a counsellor to Richard II. When Henry IV overthrew Richard in 1399 Henry was beheaded when Ralph was 20. Henry’s estates were awarded to Parliament who duly sold some of them off but remarkably Henry seemingly bore no grudges and restored to Ralph much of what had been sequestered. Ralph went on to be an MP for Northamptonshire and Sheriff of Wiltshire. He also fought in the wars against the Welsh in 1404-5. It is possible he died (disease as likely a cause as combat) during the France campaign in 1417. Despite all of this good stuff, he was never knighted, perhaps because of his father’s history.

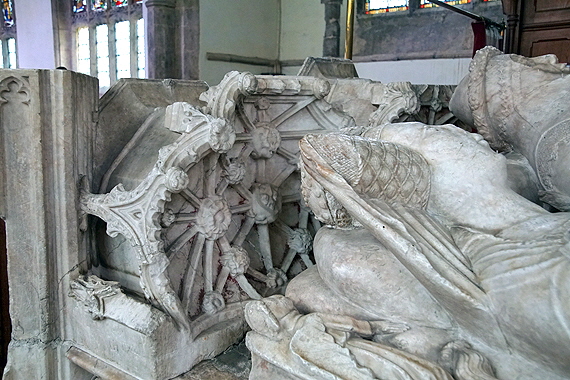

The tomb is of alabaster and remarkably the 1419 contract for its manufacture exists. Thomas Prentys and Robert Sutton of Chellaston., Derbyshire - where a lot of were alabaster was quarried - were paid £40. Ralph’s wife, Katherine, commissioned it. There are several notable things about it. The couple are shown holding hands, Ralph holding his right gauntlet in his left hand. To us that is a touching gesture (no pun intended!) but in fact it was very unusual and not necessarily just because so many mediaeval marriages were dynastic rather than romantic. In 2001 in the Guardian newspaper in an article on comparative religion the recently-deceased Don Cupitt, a Christian theology academic and lecturer at Cambridge University, suggested this was technically heretical since marriage ends at death and husband and wife face Judgment separately. Cupitt saw it as an act of humanist defiance. Whether Katherine or the masons knew this is a matter for conjecture.

By any standards, this is a sumptuous monument, the couple’s heads shown beneath representations of architectural canopies which are backed by reproductions of Perpendicular style traceried windows. The extravagant headdress of Katherine draws everyone’s attention. However, all is not as it might seem. Katherine was only thirty three when her husband died. She married again to Sir Simon de Felbrigg before 1421, very shortly after Ralph’s death,. She also outlived him, and lived to the ripe old age of seventy-six. She bore no live children in either of her marriages. In that day and age of limited contraception we must suspect she had inherent gynaecological problems She was buried alongside Sir Simon at Blackfriars Church in Norwich! Yet, the contract for the monument here shows that the hand-holding was specified by Katherine! Presumably, a grief-stricken Katherine intended to be interred here but in time found a second marriage to be expedient or perhaps she just fell in love again. Either way, Ralph is interred here but Katherine is not. Which kind of brings we romantics - and their hand-holding is seen as iconic - back to earth, doesn’t it?

Left: Ralph and Katherine, holding hands ready to face the hereafter together. Ralph proffers his bare hand, holding his right gauntlet in his left hand. He is heavily armoured and he is wearing his helm rather than resting his head on it. Right: Note the angel at Katherine’s side. Her extravagant headdress is much-admired,

Left: The tomb chest from the south. Right: The feet of Katherine show rest on two dogs.

Left: The figures of Ralph and Katherine from the vantage point of a chair! Right: Behind the heads of the couple are these finely-carved representations of Perpendicular style windows.

Click Here for a gallery containing bigger pictures of this Monument.

The South Transept Chapel

The large and somewhat empty south transept. It houses three monuments, the earliest of which is for, again unknighted, Henry Green (d.1471), Ralph’s brother. Then follows Edward Stafford, Earl of Witshire (d.1498) and finally Charles Sackville, Duke of Dorset (d.1843). The Church’s displays suggest that the transept was endowed by Edward Stafford and, therefore was not part of the original Greene church. It is plausible that the transept was a later addition. Otherwise why is Ralph Greene’s monument is between the chancel and the north chapel? Surely, if the transept was extant in his time this is where his monument would be? But surely it makes more sense if Henry Greene endowed it as he predeceased Stafford by nearly thirty years? Much more about this in my footnote. Left: The parclose screen is nineteenth century in fifteenth century style. Right: The inside of the chapel.

Top Left and Right: Tomb chest topped by excellent brasses of Henry Greene (d.1467) and his second wife, Margaret. I have seen him variously described as the brother and the nephew of Ralph. He was High Sheriff of Northamptonshire during the Wars of the Roses. He did so impartially and thus managed to hold onto what were said to be some of the largest landholdings in England. Bottom Row are the four Evangelists in brass roundels at each corner of the chest.

Left: The tomb chest of Edward Stafford, second Earl of Wiltshire. His father, the first earl, had married Constance Greene, the only child of Henry Greene - see above. Edward inherited at the age of only three in 1473. he died aged only twenty eight in 1499. In 1497 he had fought against Cornish rebels and in 1498 had entertained Henry VII at Drayton House. His wife also died young a few years later. Right: Although he is shown wearing armour and surcoat Edward is not shown wearing his knightly helm - we can see in the one of the pictures below that his head was resting on it. .

Left: The carving of Edward’s chain mail coat peeping out from beneath his armour is exquisite. Below that you can his so-called “esses” collar denoting position within the court of the House of Lancaster. Right: Edward resting on his helm.

Left: At Edward’s feet is a collared and muzzled bear. Right: On Edwards ’s feet are two “bedesmen”. Bedesmen or women (the human versions!) were pensioners or almsmen paid to pray for a benefactor. As here, they are sometimes represented on funerary monuments.

Click Here for a gallery containing bigger pictures of this Monument.

Left: The third of the south transept tombs: that of Charles Sackville-Germaine, 5th (and last) Duke of Dorset (d.1843). A career politician, he had inherited Drayton House from his father. I am sure it was seen as really great in its day - but oh what a tasteless piece of weirdness. Just a personal view, of course! Right: Funerary hatchment in the south transept.

North Chapel Monuments

Looking into the north chapel from the chancel. Under the arch you can see the Ralph Green monument.

Left: The monument to Lady Mary Mordaunt. Duchess of Norfolk (d.1705). Note the skull under her pillow! It is a naturalistic sculpture. A far cry from the mediaeval sculptures here. Right: Sir John Germaine (d.1718). What a fascinating image this one is! His wig and his armour seem quite incongruous. He holds a helm. yet armour was pretty well obsolete at this point in history, firearms having rendered it a bit pointless. I assumed he was not a soldier at all. In fact, he was a distinguished one. He was Dutch-born, however, and amassed a fortune by gambling, according to the famous diarist John Evelyn. You might wonder what his monument is doing here in Lowick? Well. he had an affair with the Lady Mary Mordaunt, the Duchess of Norfolk, shown on the left. Mary’s husband, Henry Howard was himself a notorious rake. The Howards were the noblest in the land (and fervent Catholics) so John was setting his sights pretty high! Henry was eventually divorced from her and Mary and Germain married in 1701. She had by now inherited the estate at nearby Drayton from her father, Henry Mordaunt second Baron of Peterborough. Many more earlier members of the Mordaunt family were buried at Turvey in Bedfordshire. So here we have John and Mary, not quite united in death as Ralph and Katherine Green were but still keeping each other close company!

Left: This Victorian glass at the east end has preserved the mediaeval arms of the Green family in between the biblical scenes. Right: Mediaeval arms. The plethora of armorial designs - popular in glass and on funerary monuments - was for noble families to show off their lineage and their connections by marriage.

These are panes from stained glass commemorating one Mary Dicker who died in 1909 at the tender age of seven. I do not know the significance of this representation of what appears to be a mediaeval town but I couldn’t resist photographing it.

Left: Looking along the north aisle towards the north chapel. For a church built in the early fifteenth century the aisle is quite narrow. Centre and Right: Mediaeval poppy heads, one with a mitred bishop

Left: A roof boss showing St Peter’s Keys - the dedication of the church. Right: A rather odd carving at the end of one of the roofs. The oak leaves to the left and right of this face suggest this is a slightly unorthodox green man. A tip for all church crawlers: when you see a roof with bosses that are just decorative or religious it is worth looking at the westernmost one where the roof meets the wall. There is always a good chance of an unexpected green man, as here at Lowick. Why the carpenters liked this spot so much, I don’t know.

Left: The church from the north.. Right: A cluster of eighteenth century gravestones.

Left: The south porch and south chapel. Right: This is how the church looks when you turn down to the village from the busy A6116 which bypasses it.

Left: The tower with its octagonal lantern from the south west. Right: The lantern. It is a rich composition indeed. Note the gargoyle, the little forest of pinnacles - buttressed against the walls of the lantern itself - complete with a plethora of weather vanes.

Footnote - Lollardy, Lowick Church and Perpendicular Architecture

I often tell my friends that my interest in churches takes me down all sorts of rabbit holes. Here’s another one. It came about through a coincidence. When I was writing about Lowick Church and reflecting on the almost total lack of decoration on the building itself I took a break to read a paper by Gabriel Byng called “Lydgate and the Lanterne: discourse, heresy and the ethos of architecture in early fifteenth century England”. I think Byng is probably now the most important writer on English parish churches. If that title sounds ludicrously academic then I have to tell you that the writing style is just that. It isn’t designed for the Lionel Walls of the world, of course, but to impress other Gabriel Byngs in order to acquire more academic “citations” which improve his professional standing and that of his current university employer. Bonus points are given for using words that nobody has ever seen before. Nobody would write in this style for a lay audience. But I do devour many of these academic papers as I hope is obvious to at least some of you. So what am I wittering on about?

Let’s first of all talk about the Lollards of whom many of you will have heard and about which you probably know even less than I did. It all started with a bloke called John Wycliff - yes, you’ve heard of him as well, haven’t you? Well Wycliff, born in 1324, was at Oxford University for a time before becoming a minister. He developed views that were just about as heretical as they could be. He denied transubstantiation (although he suggested Christ was present at the Eucharist) regarded clergy as superfluous to a person’s relationship with God, attacked just about every tier of the clergy and opposed clerical celibacy. He believed the Church should retreat to a position of virtuous poverty. Most notorious of all, in 1382 he was the first man to translate the Bible into English. This would allow people to understand how much of what they had been taught about Christianity was actually not mentioned in scripture. Not least, for example, was the concept of Purgatory, remission from which was such a lucrative industry for the Church. To sum up Wycliff’s beliefs, he said first just about everything that the Reformers were saying a hundred and fifty years later. His followers were called Lollards (“mumblers”) although nobody knows precisely why. Lollards were regarded as heretics although, surprisingly, by and large they were not subjected to the terrible punishments meted out to men and women with much less deviant views in the times of Henry VIII and Mary I.

One of the reasons for this was that some of what they said struck a chord not only with poor people but also sometimes with the wealthy and titled. Not least of these was John of Gaunt (corruption of “Ghent”), Duke of Lancaster, one of the sons of Edward III. John was the brother of Richard II - who was king when Lollardy emerged in the 1370s - and was also the father of Henry IV who in 1399 usurped Richard. Well-connected doesn’t do him justice and he was also probably the richest man in England as well as a distinguished soldier. Oh, and he was very much hated by much of the population! As rich men often are.

Gaunt not only tolerated Wycliff but actually protected him. Some feel he even encouraged Wycliff because he resented and probably coveted the wealth and power of the clergy. Remarkably, in 1377 Parliament (at that time, of course, not the preserve of relatively ordinary people it is nowadays) consulted Wycliff on whether the law allowed England to withhold treasure from the papacy; and Wycliff obliged them by saying it did. In a later era Henry VIII would probably have made him Archbishop of Canterbury if he hadn’t already executed him during Henry’s “Defender of the Faith” period! The Pope, needless to say, went beserk and issued four papal bulls against him but Wycliff survived and even Oxford refused to turn its back on him. All of this amounts to, if not acceptance, a surprising degree of tolerance amongst the temporal - but not the religious - powers of the day.

However, 1381 saw the Peasants Revolt, an attempted revolution that nearly toppled Richard II. John Ball was its spiritual leader, lieutenant to Wat Tyler - and a Lollard. He it was who coined the memorable couplet (taught to me at primary school!): ”When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”, thereby implying that God had never intended there to be social castes. This of course was a subversive attack on the social hierarchy, presaging the Levellers of the seventeenth century, not to mention Marxism somewhat later*.* This reduced the relative tolerance hitherto shown to the heretics. Wycliff himself, though, died peacefully enough, unburnt and with his neck unstretched, in 1384 in Lutterworth in Leicestershire to which he had retreated from the political fray. This was quite remarkable. Gaunt died in 1399, coincidentally the year of his son Henry Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the crown. With his death Lollardy’s air cover was gone.

The Lollards, however, did not go away. For sure, some who were vociferous were arrested but many went about their beliefs quietly. Perhaps crucially, Lollardy was not a Church or a religion. Adherents could pic ‘n’ mix what they believed, didn’t go around wearing badges, probably went to church as normal, and perhaps kept their thoughts mainly to themselves. I don’t know, but I suspect that they did not even refer to themselves as Lollards. They could perhaps be found in most counties but their influence during Richard’s reign was most felt in the Midlands counties, including Northamptonshire. Norfolk, Suffolk, Lincolnshire and Somerset followed in the fifteenth century. Although most Lollards seemed to have been of the common sort, some wealthy and powerful men also adopted some of their views, indeed as Gaunt himself had. Besides Gaunt, there was a group of influential men within Richard’s court - although not aristocrats - known as “The Lollard Knights”. They were also known to welcome Lollard preachers to their estates and even to force parishioners to listen to them in church. When you look at Wycliff’s principles it is easy to see that many people, rich and poor, would have seen something to like even if they did not approve of the whole package.

As an aside, it is interesting to put Lollardy into a wider chronological context. I am sure the real experts on Lollardy have already said this, but it seems to me that its rise just twenty years after the Great Plague is significant. God, it was widely believed, had sent “The Pestilence” to punish mankind for its sins. After such a cataclysm it is hardly surprising that someone like Wycliff would conclude that it was down to the perceived corruption, vanity and scriptural deviance of the established Church. Wycliff, having translated the Bible into English, would have had a keen sense of the deviances. The Plague had also more or less sounded the death knell of feudalism as chronic labour shortages and a surplus of agricultural land broke the ancient agrarian economic and social model. The habit of unthinking subservience went with it. Even in the villages men were now mostly “free” and it is hardly surprising that the freedom emboldened free thought and discourse.

In 1414, Sir John Oldcastle (Shakespeare’s model for Falstaff), a Lollard, led a rebellion against Henry V who had counted him as a friend. He had been accused of heresy and arrested. Somehow he escaped, possibly with the connivance of Henry himself, and in an act of suicidal intemperance decided to capture the king and establish a new Lollard-influenced religious and social order. The numbers involved in the Oldcastle Rebellion seem to have been tiny - between 300 and 1000 men - and the odds were ludicrous. The rebellion was easily crushed in London. Amazingly, Henry pardoned Oldcastle but he went into hiding anyway. In 1417, while Henry was (as usual) fighting in France, Oldcastle was recaptured and condemned to burning over a slow fire. This rebellion, of course, put Lollardy beyond the political pale and life became much more dangerous for Wycliff’s followers but there is no sign of a systematic pogrom. Many who were arrested were allowed simply to recant and few were burned. I think it would have been just too difficult to identify them systematically. Excommunication was a common threat. By definition, Lollards were religious people despite their anti-clericalism and to mediaeval people in general this was a terrible punishment. Burial in unconsecrated ground, for example, would be to contemplate an eternity in the flames of Hell. I don’t think it unfair to say, though, that to be a Lollard was very much less dangerous than to be a practising Roman Catholic in the reign of Elizabeth I. Did Henry V show such tolerance to Oldcastle because Lollard beliefs were not regarded as so very dreadful?

Anyway, let’s get on to Lowick and what Gabriel Byng was writing about. At last, I hear you cry!

I have already alluded a few times to the remarkable lack of decoration at Lowick Church. Stonemasons are known to have been a bit of a law unto themselves and unless they were specifically ordered not to do so they delighted in putting grotesques, heads and green men into any and all corners of a parish church. Yes, the volume varied from church to church, but Lowick, a really grand church and probably built by a reputable master of the stonemasonry craft, is conspicuous in its unadorned austerity. When it was built it seems the only decoration was probably the mediaeval glass from the previous church. “Ah”, I thought, “but it was probably painted inside as was commonplace, perhaps near-universal, in mediaeval churches”. That was until I read Byng’s article, of which more anon. Now at this point I should mention again that Northamptonshire was relatively fertile ground for Lollardy. Indeed in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries Northampton, the county town, was seen as a bit of a hotbed of the heresy. Leicester in the adjoining county was under Lollard influence very early in Wycliff’s career, and indeed Lutterworth from whence he hailed was in Leicestershire. In short, the East Midlands was “Lollard Country” if anywhere was.

Byng discusses two influential documents of the time. One is “The Lanterne of Light” which was a Lollard tract published in 1409 - note that date. The other was a poem by the court poet, John Lydgate, based on a book by an Italian author, which slightly bizarrely uses the rebuilding of Troy by King Priam to extol the virtues of highly ornate and decorated architecture as a manifestation of excellent leadership. It was probably written for Henry V while still the Prince of Wales and was published within a year or two of the “Lanterne”.

We need not discuss further the slightly weird philosophy behind Lydgate’s work - although Byng does in obscure detail - so suffice it to say that it was influential. Reading or possessing the Lanterne, on the other hand, could have you burned as a heretic. The thing about the Lanterne, though, was that it made a big point of attacking lavish architecture - the polar opposite of Lydgate’s romantic notions. The Lollards, then not only presaged similar opposition to architectural frivolity which led to widespread church despoliation after the Reformation, but also echoed the 1124 attack by St Bernard of Clairvaux - a Cistercian and the most venerated and influential churchman of his day - on what he saw as pointless and distracting church decoration. Cistercian architecture is famously austere.

It is worth noting that the Cistercians attracted a great deal of patronage at the time of St Bernard, setting a precedent for what was a series of historical resets in favour of more pious and less ostentatious religious institutions. Bernard’s attack was mainly aimed at the wealthy Cluniacs who then lost a significant amount of patronage to the Cistercians. The Reformation itself was the ultimate manifestation; and it should not be overlooked that many rich men were at that time backing the mendicant friars rather than what they saw as vainglorious and materialistic monasteries. Cromwell and Henry were not battering down a completely locked and barred door during the Dissolution, no matter what TV dramas might suggest!. And, of course, the Puritans, the Methodists, the Presbyterians were to continue this endless quest for more stripped-down spirituality. Lollardy, however heretical were many of its precepts - particularly perhaps the nature of the Eucharist - would have struck a chord with many people with its attacks on ostentation and clerical wealth. As Byng said in his paper:

“The Lanterne’s author, for all his education was writing for a wide audience. Lollardy, whatever its overall popularity and geographical spread, had traction among a remarkable range of mediaeval society range including graduate clergy, merchants, craftsmen, yeomen, wealthier tenants and even gentry and nobility - encompassing the groups most commonly involved in artistic commissions for both great and parochial parish churches” . Within the context of Lowick Church that last clause is quite possibly significant.

The Lanterne was published probably in 1409. Lowick Church was finished in 1420. One would have to say that its plainness pretty well directly reflected the views of the Lollards in general and of the Lanterne in particular. It is most certainly the antithesis of Lydgate’s romantic notions. It is difficult not to believe that Lollardy had an influence at Lowick. Perhaps the more intriguing question is whether it was patron Ralph Green, or its unknown builder who made the decision? Maybe it was both? Perhaps Ralph sought out a like-minded builder? We can never answer that with certainty but my money would be on Ralph himself being the instigator. It is hard to imagine that the master mason abstained from decoration on his own initiative. In Lollard-influenced Northamptonshire, its county town largely under Lollard influence, it is difficult to imagine that Green and his friends did not engage in debate and it would not be surprising at all if Green, even if he was not a closet Lollard, was influenced by Lollard ideas. It would not, after all, be an obvious or dangerous manifestation of Lollardy to simply refrain from decoration in his church. In case you think that lack of decoration was the norm in Perpendicular churches, by the way, take a look at the churches in my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” narrative. That work was going on no more than five or ten years before Lowick Church was built.

You might wonder if a family of wealth like the Greens would be above all this? Not a bit of it. All of our mediaeval history, especially the Reformation, is coloured by religious change and dissent. We all know that the Reformation in England was nudged along by well-placed influential men like Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell and that even two of Henry VIII’s queens - the unfortunate Anne Boleyn and the intellectual Catherine Parr - held dangerous opinions. They were not doing so as acts of rebellion or to overthrow society: they were genuinely concerned for their immortal souls. Thomas More went the other way for the same reason and paid with his life in the face of all Henry’s efforts to persuade him to compromise over the Act of Supremacy. These matters were not taken lightly. We might, in passing, compare Henry VIII’s execution of More, his best friend, with the patience shown to Sir John Oldcastle - an actual rebel - by Henry V.

The Greens would have expected to be interred in their new church and probably even hoped that its very building would buy them time off from Purgatory. No matter how heretical the Lollards were in their core beliefs the same surely could not be said for their views on architecture. So perhaps the Greens felt that a plainer, more humble building would be to their good when the Dreadful Day of Reckoning arrived.

But did Lollard influence with the Greens run deeper? When we think about the Lady Chapel on the south side of Lowick Church it is striking that the first interment there was in 1471. This suggests that it was later than the rest of the Green church, probably contemporary with the much less plain, definitely non-Lollard west tower. If it was built at the same time as the rest of the Green church then you would have expected Ralph to be buried there. And if it was not built at the same time, then why not? After all, the Greens were stinking rich. If avoidance of Purgatory was the aim then the prudent rich man of the time would have a chantry chapel built and endow it with money to fund priests to chant masses for his and his family’s immortal souls. Good location that it was, in full view of the altar, why did Ralph choose to be buried between the chancel and the north chapel? Is it because Green also espoused Lollard anti-clericalism and did not think that mass-chanting priests would help his immortal soul, perhaps even the opposite? In short, was Ralph Green after all a closet Lollard within the full meaning like some of the “Lollard Knights”?

Remember too my caption for the romantic Ralph and Katherine Green monument. The recently-deceased Don Cupitt, a Christian theology academic and lecturer at Cambridge University, suggested that their hand-holding was technically heretical since marriage ends at death and husband and wife face Judgment separately. Cupitt saw it as an act of humanist defiance - an oddly anachronistic term within this context perhaps. Was this, though, another example of Ralph Green’s religious free-thinking and indeed, since she commissioned the monument, of Katherine’s as well?

I think that in many ways, Lowick Church does us a service by highlighting the inherent austerity of Perpendicular architecture which is quite independent of the seeming determination here not to enhance it with decoration. Stonemasons had perished in common with the rest of the population. It is likely that a large number of the distinctively (but monotonously) styled windows were created at the quarry rather than on site. The soaring arcades, the huge acreages of glass and the sense of height that gives the style its name conspire to make us think of it all as rather “glorious” Gabriel Byng, however, who can be as to the point as he can be verbose, deplores in his “Lanterne and Lydgate” paper: “the tendency of historians to identify an architectural style with its most extraordinary examples rather than with the ordinary run of buildings that make up its most numerous instances in the vast majority of cases….” andhecontinues “It is evident that some late mediaeval writers, at least, had little sense of the sobriety of changes long identified by architectural historians as taking place in the decades after the reconstruction of Gloucester Abbey’s presbytery in the 1330s (and roughly, in fact, over the course of Wycliff’s life)”. For my own part, I can think of only half a dozen or less cases where, for example, that most glorious of Perpendicular features, the fan vault, appears in a parish church. Set that against tens of thousands of humdrum windows and thousands of unadorned arcades! The likes of Lavenham and Long Melford in Suffolk are the exception, not least because of the amount of money hubristic (and also Purgatory-averse) wool merchants paid for them.

Finally, returning to the question I asked myself “would this otherwise plain church have been covered in wall paintings?” My answer, in the light of all this, is “probably not”. Lollardy disapproved. Perhaps when some restoration is needed at some point in the future, painting may be found beneath all that whitewash but my money is against it. I think Ralph Green and perhaps others of his family , including wife Katherine, were at least Wycliff sympathisers to some degree.

Footnote - Our Heritage at Risk

I hope I have given you a flavour of the magnificence of this church. It is one Simon Jenkins’s Top One Hundred and for once I agree with him. It was always an extraordinary size for such a tiny settlement with a modern population of just 300! Of course, it is the epitome of an aristocratic estate church, built and maintained for centuries by the Greens and their descendants who lived in Drayton House.

I am by nature a bit of a leveller. I don’t have much truck with our anachronistic and bloated British peerage. I don’t care too much for “stately homes”. But for all of its aristocratic provenance it has been serving the parish for six hundred years and, plain as the building is architecturally (the tower always excepted) it is a repository of fine visual art - glass, stone and woodwork. The men who did this work were not themselves aristocratic: they were artisanal craftsmen of the ordinary kind. People like me and you.

So, the church is to close. How can anybody reasonably argue for its being kept open for a congregation in single figures? I am sure the Churches Conservation Trust will ensure it is preserved and kept open to visitors. It does, however, exemplify the dangers posed by church closures to our cultural heritage. Lowickians worshipped here for hundreds of years, They were baptised and buried here: probably ninety per cent of the people who ever lived in the community. Imagine this hub of village life closing its doors for ever? Imagine the glass and the monuments mouldering away in a locked and badly-maintained building, viewable by appointment only?

The problem is that when the Church of England “acquired” all of our parish churches: - all of those thousands of churches it had not built nor previously maintained - they made them theirs and not the community’s. Moreover they couldn’t wait to sell off the glebes and rectories they also acquired, forming a substantial part of that huge property portfolio you are always hearing about and which yields about half of the C of E’s £1bn annual income. Yes, you read that right. £1bn per annum. That is £1bn per annum that, believe me, is not spent on maintaining “their” churches. If your roof lead gets nicked don’t look for the C of E for help. They are worse than any landlords. They own the property but expect the congregations - whose forebears built them - to pay for the maintenance.

With congregations falling to unsustainable levels - the C of E haven’t been much good at recruitment either - and with more and more churches having to share clergy and hold fewer services, the tipping point is no longer nigh - it is already here.

And yet there is no national strategy on what to do with redundant churches. We have had reports advocating all sorts of pie-in-the-sky answers such as turning them into Post Offices (closing down at a rate of knots), hairdressers, concert halls and so on.. Take a look at the pictures of Lowick Church and tell me if you think any of those are feasible? What we have never had is any kind of Heritage Task Force to examine the problem. Simon Jenkins advocates (despite putting his name to one of the Hairdresser /PO “reports”} suggests their ownership should be returned to communities with a degree of local authority funding. It doesn’t sound the worst idea. A community that owns its church might be prepared to invest time. money and civic pride into preserving it. Myself, I believe that all churches that the C of E chooses to make “redundant” should come with an endowment from their own resources - call it a “redundancy payment”!

Can all of our churches be saved? Realistically no. If some are to close what are we to do with their artistic treasures? How do we decide what must be preserved for posterity and (sadly) what can be allowed to close completely? What do do about, for example, little Toftrees Church in Norfolk with its lovely Norman font? These decisions are going to be made at some point. Are we going to make 16,000 separate decisions without any kind of strategy or decision-making structure supported by the government and the heritage “industry”? I fear that is exactly what will happen and chunks of irreplaceable heritage will be lost to us.