Warmington

Warmington

No, it’s not Warmington-on-Sea. Stupid boy! This is Warmington-a-long-way-from-the-Sea in Northamptonshire. Apologies to overseas readers who might not “get” that quip from the wonderful “Dad’s Army”!

The church here was started in around AD1200. Alterations and additions were made later in the thirteenth century; but apart from rhe inevitable nineteenth century restoration work this is a church of the thirteenth century in a beguiling mix of Transitional and Early English styles. Pevsner described it as a “ large, noble, and stylistically uncommonly unified church.

The oldest parts are the nave arcades and - inevitably - the two lowest parts of the tower. Thus there were two aisles in this first church; but in the mid thirteenth century there was a lot of remodelling. At this point the south aisle was widened, allowing for two chapels, evidenced by piscinae and tomb recesses. The tower acquired its belfry stage and stone spire to produce a bruising stone monster so typical of East Midlands churches of this period. A little later the chancel was rebuilt, the north aisle was in turn widened and the clerestory added. And that’s about it! Even the very fine stone vaulted south porch is unaltered thirteenth century.

I have said many times on this website that the Early English style seemed consciously to turn its back on the elaborate decorative schemes of the Norman era

with its monsters and dragons, beakheads and devils. The prevalent window form was the tall unadorned lancet. We could perhaps call it a minimalist style. So stark is the contrast (and I have to say that is is strangely unremarked upon by many commentators) that I believe there must have been clerical and patronal impetus behind it all: I don’t believe the stonemasons would have so readily abandoned their drolleries if left to their own devices. Perhaps the influence of the austere Cistercians and its highly influential leader St Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) who abhorred frivolous decoration had something to do with it all? You will have seen on many of these pages that decorative exuberance broke out all over again in the fourteenth century never again to go away until after the Reformation.

So, apart from some nail head decoration around doors and windows and on the upper stories of the tower the architecture will be appreciated by connoisseurs only. The interior, however, is quite another matter! This is another of what I like to call “Church Crawler’s church” - one that has a basket of delights to enjoy.

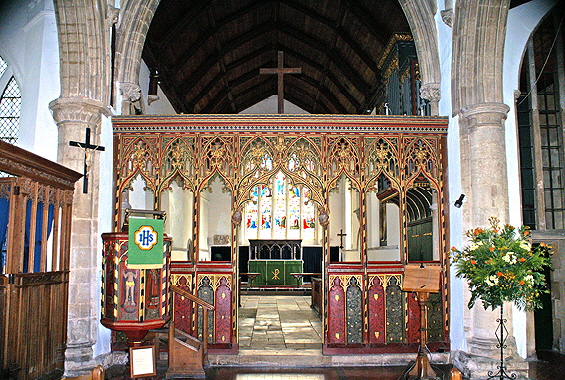

The painted mediaeval (although much-restored) rood screen will make the first impact. But then you will notice that the nave ceiling is vaulted in timber. And you might well assume if is post-Reformation, even Victorian. But it is not: it is original thirteenth century and not something I have seen in any other parish church. Not only that, but the roof bosses sport what is surely one of England’s most spectacular arrays of green men! I don’t know what St Bernard of Clairvaux would have said about that but it is possible that neither he nor, for that matter, most of his parishioners would have even been able to make out what they were. Which is my way of telling you to take binoculars or a telephoto lens for your camera! They are unpainted and determinedly grotesque. No two are the same and there is even what might be a green woman, forsooth. There is a lovely painted fifteenth century wine glass pulpit that the epic grump Pevsner decreed to be “over-restored” but which will delight we lesser mortals.

Finally, and oddly, there are two bench ends with House of York symbolism that other commentators have strangely overlooked. My eyes are on Fotheringhay for their original location. More on this anon.

Left: The later thirteenth century bell stage of the west tower and its stone spire. with three sets of lucarnes. George Gilbert Scott felt it was a perfect example of its type. Note that it is a “broach” spire where a spire of octagonal plan is placed on a square tower using those odd little corner pieces known as “squinches”. Centre: The bell openings demonstrate the extraordinary advances made since the Norman era. Note the head of the arch with its plate tracery. It is not tracery at all as we would know it but the thirteenth century builders presaged it by cutting designs - in this case a quatrefoil - straight through the solid stone at the head of the arch.. Note the shallow inverted triangular corbels just below the spire - a characteristic of broach spires in the East Midlands. Right: Lucarnes of about 1275 on the spire.

Left: A triple lancet window, almost the definition of Early English architecture on the south aisle. This arrangement, however, is much more common on east windows than on aisles. I surmise that the original east window here would be have been one such. This is a particularly rich example with a double hood mould, decorated “capitals” on the colonettes and two courses of distinctly Norman-looking zig-zag. Centre: The south porch with its stone vault and Early English south door within. It is a architecturally perfect. The course of dog tooth moulding casually references the decorative courses around Norman doorways but the multiple “engaged” (ie attached to a wall) colonettes of the porch entrance paint a very different picture of big advances in carving, stone and mortaring. Note the benches to either side. The porch was not there just to keep rain off your head! A porch in an English mediaeval church was a place of business, lay and religious, and parts of the baptismal and marriage ceremonies were performed here Right: The west door, again, nods towards Norman decorative practice but the ogee arched, somewhat Moorish, head of the arch is sophisticated and cosmopolitan. Note the large filled-in window above in a similar style,.

Left: The view to the east with its pretty screen. Pevsner deplored the wooden vaulted ceiling as “disappointing” but I am presuming he meant the one in the chancel, not the thirteenth century one visible here in the nave. Note that even though the arcades are contemporary with each other one side has octagonal columns and the other side has round ones. Centre: The remarkable thirteenth century wooden vaulted nave ceiling. It is fortunate that the clerestory is of the same date otherwise the ceiling would certainly have been lost to us when one was installed later. Perhaps that is why such ceilings are vanishingly rare? Right: The ceiling is carried on these little colonettes with faces and decorative capitals at either end.

Left: Looking towards the west. The tower arch, undoubtedly an Early English one is hidden behind the organ. Right: The chancel, it must, be said is disappointingly plain. It is mid-thirteenth century but was altered a lot a century later. Most of the east end was rebuilt and it is something of a mystery why the east window is off-centre. The north wall is original but the south wall dates from the fifteenth century alterations. It does not look quite right for the mid-fifteenth century so I wonder if it was replaced during the Victorian restoration? It is similar to the south windows. Note the carving just visible at the north east corner - more on this below.

Left and Right: The screen adds a welcome splash of colour to the Early English plainness. Some of it is of the original fifteenth century but the delightful tracery was mostly - but not all - restored in 1876. Doubtless the dado panels originally had images of saints or apostles that were erased after the Reformation.

The these two bench ends weer “omigod” moments for yours truly. On the left is a falcon within a fetterlock. This is the symbol of the House of York. Centre: Is a boar. This is another Yorkist symbol and was the personal symbol of Richard III. As far as I am aware, nobody has previously commented upon their presence here. It is extremely unlikely that they were here originally; much more likely that are from Fotheringhay Church less than three miles away. It was a collegiate church and at the Reformation the “college” - a group of priests probably spending a lot of time praying for the souls of York family members, alive or dead - was dissolved. At that point its chancel was demolished, the rest of the church remaining as the parish church. When the demolition occurred it was presumably decided that the stalls for the canons were also surplus to requirements. Hence the rural Northamptonshire churches of Hemington, Tansor and Benefield each acquired some. Hemington got - to our modern eyes - the best of them: including more falcons in fetterlocks and a misericord showing two boars. It is pretty obvious that Warmington acquired these bench ends from Fotheringhay too. All of the misericords are on this website - just follow the links in this caption box. Right: The very pretty “wine-glass” pulpit of the fifteenth century. The painted figures are, of course, modern replacements for those erased at the Reformation. It matches the screen beyond beautifully.

Left: Angel carvng on an arcade spandrel. Right: A little bit unloved perhaps, but providing a useful table for a side altar in the north aisle, is this tomb chest of the late fifteenth century with polished black stone lid. Brass indents have been lost.

This thirteenth carving now located to the left of the altar on the east wall is the greatest treasure here. The figure on the left is piercing herself with a sword. The rest of the carving is frustratingly difficult to understands but I think we can assume that is a demon behind her and it looks like he is tugging at her braided hair. Nor is it clear what was the original context of the carving. Were there others?

The nave ceiling bosses. Is this the finest set of green men in England? Certainly, I would imagine for the thirteenth century. This, by the way, is the full set. I am not sure what commentary I could usefully give so make of them what you will. I would only point out the very strange one second row right which looks like a woman in a wimple. Or even, just possibly a scold’s bridle. Most bizarre of all, is it a green NUN? Either way, they don’t come much weirder than these. What fascinates is that there are so many of them. This does not suggest simple re-use of the old (alleged) fertility symbol. This suggests a carpenter who wanted to make a gallery; a sort of artistic statement. There are other “sets” of green men but I can’t think of any as large as this, as early as this, or as weird as this.

Left: The unexceptional font is mediaeval and set on a base of 1662. Centre: Having said that the church is conspicuously lacking in decoration, I have to confess to a series of these quite Norman-looking corbels in one of the aisles. Right: The north side. Note the windows of the aisle and of the clerestory: All are in the their original late Early English / early Decorated style/ Although they are hardly spectacular, this is an extremely rate example of a full set of windows of this period and they are very much of apiece with the top sections of the tower and its spire.