Wirksworth

Wirksworth, Derbyshire

I don’t often quote Simon Jenkins but he has the appearance of this church spot on : “(it) rises pink and dark in the centre of the town, its pink stone discoloured by soot like the hide of a wild boar” . As you approach it through a narrow side road, its south side looms ahead of you, blocking the view, in a way reminiscent of many a French town, or even the approach to Petra in Jordan (also hewn from pink stone). As with that recently-recognised “Wonder of the Modern World” what lies beyond the narrow approach is an unexpectedly substantial space. The church sits proudly and immovably within it.

This is a substantial building with long aisles and substantial transepts to north and south. Its windows - with the exception of the chancel - are a mixture of uninspiring Perpendicular style designs. The seasoned church crawler will, however, quickly spot the cruciform shape of this church and know that all here is not as it might seem and that a Norman or Early English core lurks within.

It’s a dark old place within. The clerestory - added by George Gilbert Scott in 1870-6, is too meagre to flood the nave with light. Lots of rather mediocre Victorian stained glass doesn’t help. But once your eyes have adjusted you quickly spot the great central crossing that supports the later tower on massive thirteenth century columns. This Early English provenance continues into the chancel with the Early English lancet

windows of its north and south walls. The east window is Victorian but predates Gilbert Scott. The harmony of the church was not well-served by two nineteenth “restorations”. The aisle arcades are, according to Pevsner who knew about these things, slightly later than the crossing.

As with so many churches, however, the structure of the church is not what would bring you here. The greatest treasure is one of the finest surviving Anglo-Saxon sculpted coffin lids in England. We are used to seeing pre-Conquest coffin lids, especially in the north of England, adorned with crosses, swords, shears and so on. This one is quite something else, adorned as it is with Biblical scenes and more or less intact. It surely adorned the coffin of someone of high status, probably a Bishop. It is wall mounted in the North aisle. For something as good (but very different) you probably need to see the one at St Peter’s Northampton.

So we can be pretty sure that there was an Anglo-Saxon church of some kind here. That the existing church was not the first here is spectacularly confirmed by a host of Norman fragments built into the walls and by the simple Norman tub font that, somewhat prosaically, has been replaced by a military medium octagonal affair of 1662. Still, if the Norman font was discarded into the churchyard or some nearby farmyard, as was so often the case, it is at least now returned to its rightful place, if not to its rightful function!

It will surprise many visitors to picturesque and rural Derbyshire that the county was always the centre of the mining industry. Whereas coal was the product of the southern part of the county - part of the Notts, Lincs and Derby coalfield of my early life - many other mineral resources have been tapped in Derbyshire, of which the most important surely was lead. It is a little-known fact that Britannia was the most important source of the metal in the Roman Empire, Derbyshire flourishing along with locations such as Cornwall, Cumbria and the Forest of Dean. Indeed, many an English parish church acquired its lead from Derbyshire, the material moving along the River Trent, the (Roman) Fossdyke and the River Witham to the principal lead market at Boston in Lincolnshire, from whence it could be re-shipped by sea or other rivers such as the Welland and the Great Ouse. One of the most famous carvings here at Wirksworth is known locally as T’owd Man”, a depiction of a lead miner with his pick and a bucket, or “kibble”. Again, this carving substantially pre-dates the church we see today.

Finally, there are a few really good monuments here, some in that other - expensive - Derbyshire mineral : alabaster.

Looking east through the Early English crossing to the chancel beyond. The east window is early nineteenth century although, to be fair, you would hardly know it. You can easily see an earlier roofline above nearest arch. It would have been raised to facilitate the building of the much-needed clerestory by George Gilbert Scott. In truth, it is not man enough to illuminate this lofty nave. At this point, I should point out that it was necessary for me to raise the exposure of many of my photographs for this web page,

We may as well cut to the chase. This is Wirksworth’s “main event” - no insult to t’owd man. There are eight scenes depicted here. According to the leaflet produced by the church itself, it was found when the pavement in front of the altar was being dug up during the 1820 restoration. It covered a stone vault containing a perfect skeleton and they believe it to be that of Betti, one of four missionary priests sent from the Kingdom Northumberland to the Kingdom of Mercia in AD653. Mercia was the last of the large constituent kingdoms that eventually became “England” to convert to Christianity. By which we really mean where the kings last converted to Christianity!.Wulfhere was its first Christian king, ruling from AD658-675 so perhaps it was these missionaries that made the difference.

Left: Christ washes the feet of his disciples (stage left). To the right the four evangelists in their iconic forms and holding books surround a cross (described by the church as “Grecian”). In the centre of the cross is the Agnus dei - the Lamb of God. Right: St John leads the procession of the body of the dead Virgin Mary, holding a palm (central figure standing). The other apostles carry Her on a stretcher. Have you ever thought about how Jesus’s mother died? Me neither. My Sunday School “didn’t go there” but we were told about “The Assumption” where she ascended into Heaven, seemingly as a live rather than a dead person. The Roman Catholic Church (please don’t be offended!) created a whole “story” about the life of Christ’s mother, none of which appeared in the Bible. The Eastern Orthodox Church created their own narrative, entertaining the idea of a “natural death”, also followed by an Assumption. The killer is that The Bible doesn’t discuss how or when she died at all! Yet here at Wirksworth we have a whole narrative being played out and, perhaps oddly, in a scene that seems more Eastern Orthodox than Roman Catholic! The Church Guide says that the the lower of the two recumbent figures is The High Priest being dragged along after “seizing the bier”. I don’t know the story behind that. To the right of St John is allegedly of Christ’s presentation at the Temple (in these fevered times, we perhaps need to reminded that Christ was born and died a Jew), Simeon holds Christ in his arms (you can see his little face). You can also see the hand of God to the right of Simeon’s shoulder. A broken off image of Mary was supposedly on the right.

At the bottom left (again, I could not possibly have interpreted this myself so hats off to whoever did) Herod, Judas Iscariot and Cain burn in a brazier. Their crimes were so heinous that they could not be spared when Jesus above their heads was releasing Mankind in the form of a baby wrapped in swaddling - the Descent to Hell.. Don’t look for this in the Bible either. A non-Christian myself, I could never “get” the Judas thing. Christ knew in advance he would betray Him and could have forestalled him. If JI was just fated to play a part in the whole Crucifixion story - and how many countless other people have before and after have sold out for forty pieces of silver - why could future Christians not follow Christ’s teachings and forgive him? Not trying to be Richard Dawkins here or to question the Christ story but I am endlessly intrigued by the contradictions of the man-made narrative of Christianity, some of which appears on this coffin lid. I suppose it is around such “filling in the gaps in the narrative” that the many sub-sects of Christianity coalesce. To the right of all that we have Christ’s Ascension (at last, something Biblical!) surrounded by four archangels with Mary and St John giving a helping hand from below. Somebody somewhere must know why Christ “ascended” and Mary was “assumed”. I guess it is a case of Christ having done it of his own volition and Mary having been a more passive player.

Left: The archangel on the left is greeting the assumed Mary who is seated. On the far right St Peter (probably) stands in a boat ready to go off and take the Word to the gentiles. Mary is next to him, holding the infant Jesus in her arms. I confess I struggle to see that myself and I so admire the scholarship of those that can - seriously. Presumably the guys to the left are other disciples. Right: The view to the west.

A little array of sculpture preserved in the walls of the church. I do wonder if they have been assembled here for centuries or if Gilbert Scott collected it all together during his restoration? You can see very obvious Norman sculpture here, like the pieces of beakhead carving. I particularly like the rather jolly-looking dragon or beast peering over his shoulder. The piece de resistance here, however, is the so-called King and Queen of Hearts (right). My question here is whether it is actually Norman or pre-Conquest? Pevsner declares it all to be Norman but I am not sure how would could know (and Pevsner never did take a lot of interest in sculpture) but to me it looks earlier. The heart shaped body of the Queen is seen by some, including the Church Guide, to suggest this is the King and Queen of Hearts but that seems to me to be fatuous and it is more likely that the sculptor just used the shape for her body. I am also interested of where this piece came from? Unlike the other pieces here, It is too big to have been on a Norman corbel.

Left: “T’owd man” with his pick and metal buckey. To the town of Wirksworth it is something of an icon. Right: The original Norman tub font.

Left: The east end of the north aisle contains two tomb chest, both of alabaster. To the left is Ralph Gell (d.1564) and his two wives. To the right Anthony Gell, Ralph’s son Right: The ends of the two Gell monuments. Note the more elaborate sculpture of Anthony’s monument, just a generation later.

The Ralph Gell monument is a so-called “altar tomb”, flat topped and in this case with an incised slab.

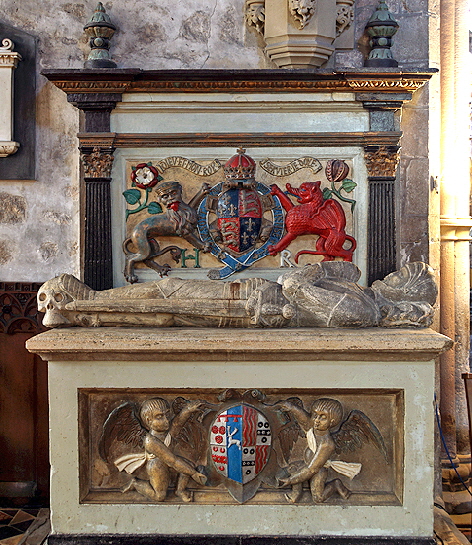

The Anthony Gell (d.1583) monument, vastly more elaborate than that of his father.

Left: “Weepers” on the north side of the Anthony Gell monument. These are not the most finely-carved of features. Right: The striking monument to Anthony Lowe (d.1553), a courtier of five Tudor monarchs starting with Henry VII, his head resting on a strikingly large skull.

Left: Sir Anthony Lowe’s tomb of which Pevsner said “already in the new renaissance style”. Note the Corinthian capitals to the canopy. Lowe is in armour, his helm raised. Centre: Another view of Anthony Gell. He is bare-headed in fine flowing robes. Right: This funerary slab has brasses to Thomas Blackwell (d.1525) and his wife as well as figures from another Blackwell brass.

Left: Head of Sir Anthony Lowe. Right: Female weepers from the Blackwell brass. It appears that the unfortunate woman bore eighteen children.

Elements of the Blackwell brass.

Left: This rather nice wall monument was erected in 1719 but commemorates John Lowe who died in 1690 aged 39 and his sister, Elizabeth, who died a widow in 1713, aged 62. Just look at that skull! Centre: The chancel with the Sir Anthony Lowe monument to the right. Right: Looking along the south aisle.

Left: Massive stone coffin outside the church. Centre: The south transept and tower looming at the top of the narrow approach lane. The town museum is to the right. Note the balustrading on the top of the tower, a pleasant alternative to the usual battlementing. The little lead-covered spike, however, is something of a laughable addition Pevsner called it “an exceptional addition” but I like to think it meant that literally rather than in the alternative meeting of superb! Right: The south transept with a fine Perpendicular style window. How old is it? Probably Victorian, I think.

Unlike with many rural churches, the church crawling photographer gets largely tree- and junk-free views of all aspects of Wirksworth Church seen here from (left) the north west and (right) the west. The west window is notably large. The rectangular ones of the north aisle could be charitably described as “unfortunate” but it also retains a couple of Early English lancets. Of particular interest is the steep roofline showing on the west side of the tower. It is considerably higher than the Gilbert Scott clerestory and of the roofline visible above the chancel arch within. Was there an earlier clerestory?