Schlepping Around Sheppey

When I did a tour of Kent churches in 2025, Minster in Sheppey Church was on my shortlist of visits. Despite several trips to Kent, I had never ventured onto the island. I have since found that hardly anybody I know has either, including people who are or have been living in Kent! The island is in the north of the county located on the south bank of the Thames Estuary. It is now connected to the mainland by the Sheppey Crossing, a quite impressive bridge opened in 2006. Prior to that you had to to use the much smaller Kingsferry Bridge, shared by road and rail, which had a lifting mechanism to allow the passage of ships. “Isle of Sheppey” means Island of Sheep, which befits a low-lying, marshy tract of land. Minster in Sheppey, the main town is situated on the highest point of the island - all of seventy five feet above sea level.. Economic activity is limited but there is a port and a dockyard at Sheerness at its north east point as well as three prisons of various categories at Elmley, Standford Hill and Swaleside.

The island is only thirty six miles in area. At one time there were actually three islands but the silting up of the river channels eventually reduced it to one.

Being situated where it is, within short sailing distance of London, it has an interesting military history. Vikings first arrived in AD835. In AD855 it was an over-wintering site for a Viking force. In the eleventh century King Cnut retreated here during his conflict with Edmund Ironside. In 1667 the Dutch in one of several humiliations for the Royal Navy at that time, as memorably recorded by Samuel Pepys, captured Sheerness and occupied it for a few days. James II, fleeing from the Protestant insurgent William of Orange (those pesky Dutch again!) after the Glorious Revolution in 1688 - which was inglorious in the extreme for poor old James - was captured by the locals at Elmley and despatched to Faversham on the mainland.

The naval dockyard was decommissioned in 1960 but Sheerness still operates as a civil port, and is important to the island economy. A bizarre fact about the island is that it is home to Britain’s only scorpion colony - the European Yellow-tailed scorpion. It is hardy, small, shy and its venomous sting is said to be less painful to humans than a bee sting. I don’t intend to test it. Its colony is in Sheerness Docks where it was likely to have been “imported” from a ship. I bet it was those bloody Dutch again!

There are few churches. Minster in Sheppey is much the largest, the little church of Harty at the eastern end of the island is the most lovable and has, in my view, its greatest treasure. Only Minster is what we might call a “Destination Church” , although Queenborough is another - somewhat surprising - entry in Simon Jenkins’s book. But all of those described here are of interest, often with nautical connections. It is good to venture off the beaten path sometimes and The Isle of Sheppey is certainly that despite being so close to the populous Medway Towns with London not too far distant.. As ever, I like to champion the under-recognised little gems of our parish church heritage. I am going to cheat by including the church at Bobbing which is actually on the mainland, about three miles from the bridge. But we visited it en route to Sheppey and I love its name so I have annexed it to the island. Such is the awesome power of a webmaster.

Bobbing

Dedication : St Bartholomew Simon Jenkins: Excluded Principal Features : Romanesque Sculpture; Monuments

I am going to be perverse and start with the church that is not actually on the Isle of Sheppey but which is very close to the Sheppey Crossing. Architecturally, it is a pretty little church, its neatness somehow in keeping with rural Kent’s feeling of easy prosperity and good order. You can date much of it to the early fourteenth century by the nice Decorated style windows with curvilinear tracery. The oldest part is the north aisle which was probably built in the first half of the thirteenth century. The whole lot was restored in 1869 but this is not apparent,

The treasures are, however, within. There are two memorable wall monuments, including one to two Parliamentary soldiers who were brothers. There is a fine brass.

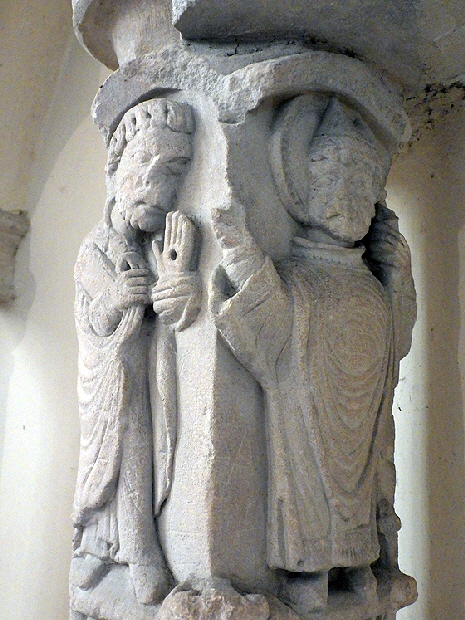

Best of all. are the extraordinarily rare Romanesque sculptures incorporated into the western column of the triple sedilia inside the chancel. They are, of course, evidence of an earlier church so presumably the north aisle was an addition to that earlier building. These represent St Martial - of the third century AD - and a deacon whom the saint is ordaining. They are standing on a little square-profile column that has Romanesque decoration but which may have been carved later for the purpose.

Bobbing is a pleasant, airy church, enhanced by the king-post roof that is typical of this area. On you way to Sheppey or on your way east from the Dartford Crossing towards Canterbury and Ramsgate, it is well worth calling in.

Left: Looking to the east. Note the king post roof to the chancel resting on a wooden beam. There is no sign of a rood screen having been here so one most suppose that all trace was removed during the Victorian restoration, leaving a particularly airy feel to the east end of this church. Note the wall tablet to the right, of which more anon. Right: Looking towards the west end with its high, narrow arch, possibly of late thirteenth or early fourteenth century origin. Note the wall-mounted brasses to left and right of the arch..

Left: The mounted brass of Sir Arnold Savage (d.1410) and his wife. The height of Sir Arnold’s figure is 3’6”. Centre: The wall tablet to Charles Sandford (d.1660) and his wife, Elizabeth. Pevsner unkindly described them as having “coarse, pudgy features”! Less remarked upon is the carved legend. He was the “receiver” of the counties of Kent, Sussex and Surrey for King James (the first) and Charles I. It continues “save in the late years of Anarchy (ie The Commonwealth) when he rather chose to part with his office from his loyalty but lived to see restored with honour upon his majesty (ie Charles II) happy restoration. Let others speak his bounty, zeal and love, three royal masters prove”. A staunch royalist then which is a contrast from those depicted on the other wall tablet (Right) to Charles and Francis Tufton. Charles died in 1652 aged 24, Francis in 1657 aged only 21. They are both dressed in what appear to be uniforms of Cromwell’s New Model Army. Dying so young, one might have expected that one or both died in battle but both died after the end of the Civil War in 1649. There was an Anglo-Spanish War in this period but although there was much naval fighting around Kent, there were no land battles. The extensive inscription talks mainly of their lineage and one must suppose that any military death would have been mentioned, even glorified. So one must suppose that, against all expectation, these two likely lads died of natural causes or disease.

Left: On funerary brasses - indeed on some funerary stone monuments - what is at the deceased’s feet can be as interesting as the rest of the figures. Here a particularly pussy cat-like lion lies at Sir Arnold Savage’s spurred and armoured feet, hinting at the man’s valour. Right: The Brothers Tufton in the uniform of Cromwell’s New Model Army.

Left: The carving of St Martial (right) blessing a deacon (left). The renowned George Zarnecki, the doyen of twentieth century commentators on the Norman period of English church architecture, dated the sculpture to about AD1190. Centre: The deacon. Note his robe, the book (Bible?) he holds and - unaccountably - the neat hole in his hand! Right: The pedestal upon which they stand is decorated with designs that would have been right out of the 1190 Design Book (had there been such things). These are sophisticated designs that could have adorned the decorative courses of a late Norman or Transitional doorway. They look too fresh to be original - but it is eminently probable that they are just that.

Left: The face of St Martial. clutching his crozier…perhaps? Note the halo. Note also his name inscribed in Latin above his head, Right: The Decorated style triple sedilia. The Romanesque sculpture has been set into its right hand support. A bishop is set into the left hand end stop with a rather jolly-looking peasant on the right.

Queenborough

Dedication : Holy TrinitySimon Jenkins: * Principal Features : Painted Ceiling

You would not expect the name “Queenborough” to be random and it isn’t. It is named for Phillippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III who built a castle here between 1361-77 to defend against the pesky French. Its design was unique in England until its demolition sometime after the end of the Civil War. It was built of concentric rings of defences and was state of the art at the time. Edward stayed several times in Queenborough during its construction.

The church is a quirky one set in quirky little town. This is not the so-called “Garden of England” to the east. It is not full of gorgeous and expensive period houses and cottages surrounded by lush greenery with oast houses poking their heads proudly above the comfortable, prosperous villages. Queenborough is a working town, its character defined by its insular position and the hard lives of those who once earned perilous livings at sea. The church was started in 1366, so its building it was contemporaneous with the castle. Edward paid for it and Pevsner marvelled at its simplicity, considering its royal patronage.

There is no separation between nave and chancel and it seems there never was. There are no aisles. Its west tower is somewhat oddly proportioned with a slightly bizarre polygonal bell turret. All of the windows were replaced in 1885 and the quirky but not unattractive dormer window was installed at the same time just to the right of the south porch. The only treasure here is the ceiling which was boarded in 1695 and painted with angels and clouds. That’s about it, really! But those paintings are worth seeing.

Left: Looking west towards the lofty tower arch. .Right: Looking towards the east end. If the east window was replaced in 1885 along with the rest it was nicely done, although its style is perhaps a few decades out of kilter with the church’s building date.

Angels adorn the boarded roof ceiling of 1695. It must have seemed pretty flamboyant for the time. William of Orange had ousted the last Roman Catholic British monarch James II in 1689 after the Glorious Revolution. This painting doesn’t look terribly Protestant. It is believed to have been painted by an unknown Dutchman. Well, the Dutch were protestant all right! The Netherlands was not a good place to be a Catholic at that time.

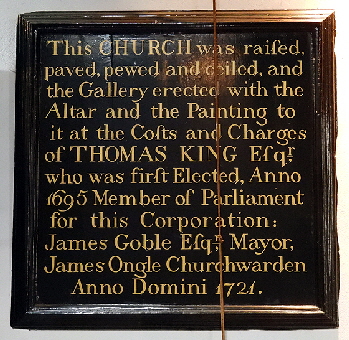

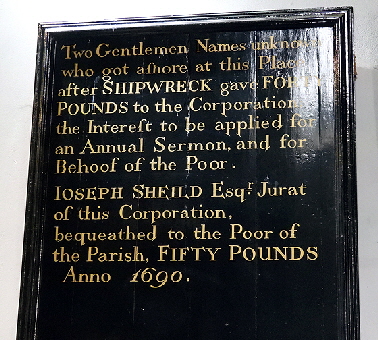

Left: Thomas King, then was responsible for the ceiling. But the board is dated 1721 and it was King’s election to MP that occurred in 1695. Centre: You can read this for yourself, but what a wonderful piece of local history this is. Right: The arms of Queen Anne dated 1713. The human-looking head on the lion is not just whimsy: it is the face of the executed King Charles I who gave the town its charter.

Left: The odd little church tower. To my surprise, Simon Jenkins includes the church in his celebrated “Thousand Best”, citing the painted ceiling and the “panoramic tower view” which, I guess, is not available to the rest of us! It caught fire in 1933, burning all of the original fittings. Centre: Hasn’t St Francis come to the wrong church? Well, I guess we all love Frank but this is, after all, a C of E church! What would William III have said? Right: Unfortunately I did not make a note of who this gentleman is who hangs near the south door.

Left: St Francis, charmingly, feeds a Blue Tit and…er…another sort of tit. I think. Right: Memories of the sea in the churchyard. The Church Guide says, rightly, that many a sailor would have married his love here..

Eastchurch

Dedication : All Saints Simon Jenkins: Excluded Principal Features : Livesey Monument

By Sheppey standards this is quite a bustling town, the church at its centre. In truth, it is not going to be worth a detour except for the real monument aficionados but it is en route from Queenborough to Minster-in-Sheppey - the biggest church on the island - and to Harty, my personal favourite.

It is a foursquare place externally, originally built in 1431, restored not drastically by the Victorians, and pleasant enough to look at. I was a little bit startled to read that the south porch arch is of stone from Clipsham in Rutland, about whose church I have recently written. There are or have been many high quality stone quarries in the area but I would not have expected to see the stone transported this far!

The interior is bright and decent but totally unexceptional. The best things here are undoubtedly two monuments.

The most obvious one is to Gabriel Livesey (d.1622) and his wife. This is a fine piece with some interesting features. Wifey - with a somewhat pudding face, leans over and looks at her sleeping husband, presumably checking the bedside clock while her hero lies sound asleep dreaming of we know what. Unusually, he clutches a book in his left hand. He also sports the most curious footwear! At his feet is the headgear (and scalp?) of a “Saracen”, a popular affectation for the stay-at-home, don’t-ask-me to-carry-a-sword-I’ve-got-a-bad-back administrator of his day. We don’t know much about him but his son, Michael, signed the death warrant of Charles I which resulted in the usual hunted life of a regicidal fugitive when the vengeful Charles II came to the throne. He is believed to have died in Rotterdam.

The second monument of interest is a wall monument to Sir Richard King (d.1834). Pevsner describes it thus: “The fine relief shows, rather strangely, a man o’ war half-draped with a voluminous sail”. It’s not so “strange” when you find out that King was actually an Admiral at his retirement and had served in the Royal Navy for a staggering sixty years as well as being Governor-General of Newfoundland! He commanded six ships and was C-in-C, Portsmouth as well as serving as an MP after leaving the navy. The monument shows the prow of a ship of the line with two cannon poking from gun ports and a couple of cannonballs to boot. So there is interest here for the naval historian.

Left: The view to the east. The screen - unusually outside the south-west - spans both aisles as well as the chancel. Right: Gabriel Livesey and his wife. “Gabe, Gabe, are you awake yet, baby? I know you are just pretending….”. Note the book in Gabriel’s hand. It was obviously a boring read.

Left: The Livesey monument in fine Jacobean style It has Corinthian capitals to its columns. Note the niches in the tomb chest showing just two children: a kneeling boy and a recumbent infant (Right Upper). Right Lower: The Saracen’s head much of which seems to have been hacked off..

Left: The son of Gabriel Livesey - a young man, it seems. Right: The wall monument to Sir Richard King (d.1806). Remarkable to us now (but not so much then) was that he joined the Royal Navy in 1738, aged eight! Perhaps he was a “powder monkey” serving the guns with gunpowder in battle? He was a Lieutenant just seven years later.

Minster in Sheppey

Dedication : SS Mary & Sexberga Simon Jenkins: *** Principal Features : Monuments & Brasses; Gravestones

Minster is by some margin the most interesting church on the island. The abbey here was founded by Queen Sexburgha of Kent (there was no “England” in those days remember) in AD664 - the year of the Synod of Whitby where the Celtic form of Christianity lost the argument against the Roman insurgents. Perhaps this was no coincidence. Remember that St Augustine had been welcomed to Kent from Rome in AD597 and he would have had little time for the simple monkish practices of northern England.

The Vikings - predictably - sacked the abbey in the ninth century. It would have been a sitting duck for the Danes as they marauded up the Thames Estuary. William the Conqueror partly rebuilt it and Archbishop de Corbeuil finished the job, rebuilding both the priory and its church in the twelfth century. The priory church was not, however, a parish church and late in the Norman era a second church was built adjoining the priory church to the south. Thus we still have a double church as can be seen in the picture (left).

The nuns and the parish would have conducted their masses completely separated from each other. Surprisingly, however, the arcade between the two churches also seems to have been made in the thirteenth century. Were there wooden barriers between the nave arches perhaps? At the Reformation the priory was closed and its belongings sequestered. As you would have expected the parish church survived intact but more surprisingly the priory church was not demolished or diminished.

The nuns’ church to the north still has traces of the Anglo-Saxon structure. The parish church is in the thirteenth century English style with its triple lancet east window and a single surviving lancet to the west. However, its south door is in Transitional style, with a rounded arch suggesting that that it was all very early twelfth century. None of that, however, squares with the suggestion some have made that de Corbeuil - who died in AD1139 - built this church. The obese little west tower dates from fifteenth century.

I have not seen a convincing explanation about how the two churches worked together. Why was the parish chancel built without a chancel arch to facilitate a rood screen, of which there is no sign? Why was an arcade built which would have allowed free passage between the two churches? We would certainly not have expected nuns to be worshipping alongside parishioners. Is it possible that the priory church simply became the north aisle to the parish church with the nuns confined to their eastern St Sexburgha Chapel? This idea is undermined by the building of an arch between the two chancels in the fourteenth century. I am baffled.

The interior of the church, to be honest, has a scruffy feel to it. It is cavernous and dark. There are several monuments to be seen, all meticulously researched and explained. For some reason, however, most of them are battered and they have all suffered the worst attacks of grafitti-carving I have seen. These are not, in the main, modern depredations and we might reflect that vandalism is not just a modern phenomenon. Indeed, churches seemed to have suffered more from this than they do today. Perhaps in previous centuries the parish church was the only place worth their attentions. There are some fine brasses to see too.

There are unheralded gems to be seen in the churchyard. At some stage, all of the older gravestones - mainly eighteenth century - were placed around the perimeter of the churchyard, for all the world like a wall of gravestones. Most visitors, I imagine, walk right past them. In Sheppey, it seems, there was one or more memorial stonemasonry “shops” that were ambitious and highly skilled in their work. In particular, they pandered enthusiastically to the morbid and somewhat macabre preoccupation of the time with doom and death. Sculptural carving on churches was in full retreat at this time. The appetite for the grotesque and profane had been driven out by the scripture-obsessed zealots. It is no surprise that the skilled stonemason should instead focus his creativity on monumental stonemasonry where the patrons called the tune, not the priests.

Left: The east end with the Early English parish church on the left and the (somewhat bashed about) Norman priory church to the right. Right: Looking east in the parish church. It is without a chancel arch or any vestige of a rood screen. This begs questions as to how the dual church actually worked with regard to worship.

Left: Looking wast in the nuns’ church. The chancel was remodelled in the early fourteenth century, its width increased to match the nave. Both the chancel arch - as crude as it is massive - and the arcade are thirteenth century. Right: In the wall dividing the two churches we can see the obvious signs of the Anglo-Saxon structure. The window heads incorporate Roman tiling as was fairly common in early churches as in Brixworth in Northamptonshire. Note the height (not necessarily the tallness) of these windows - another pre-Conquest pointer. This wall then is the original south wall of that original church.

For a large gallery of Minster in Sheppey pictures and further information please Click on this link

Harty

Dedication : St Thomas the Apostle Simon Jenkins: Excluded Principal Features : Remote Location; “Flemish Kisk”; Modern Glass

Minsterites might recoil in shock but Harty, in my view, is the most rewarding church on Sheppey. Its location feels like it is one of the ends of England, which arguably it is, but its feeling of remoteness is just that - a feeling - because this is Kent and you can be here from London in an hour. I choose the churches I write about with a mixture of whim and a touch of resignation: some churches just demand to be written about because of their renown or on account of their treasures without always stirring my emotions. Some churches I photograph a little superficially (by my standards) because I know they are never going to make the cut. There are many fewer where I walk in and know that writing about it will be an inevitability because it immediately captures my heart. One such was Harty. And that pun was unintended, by the way!

Harty was an island in its own right and was separated in the time of Edward I by a channel up ti a mile wide. Now the creek is just a trickle with a causeway between Harty and Sheppey. AD835 saw the Vikings sack Sheppey and presumably Harty too. in AD855 Vikings overwintered. The Northmen were transforming from raiders into would-be occupiers. Not far beyond the north walls, clearly visible, is the estuary itself.

The first church here was probably of two cells. But when was that first church constructed? The Church Guide talks of Saxon origin. Its evidence is the thickness of the nave walls that are somewhat thinner than the 2’6” regarded by Taylor & Taylor as being the bare minimum for a Norman church. They point also to excavations in the south wall showing “Saxon work”. That seems to be the limit of the evidence. Pevsner - who probably would not have measured the thickness of the walls - makes no

mention of pre-Conquest work. Crucially, the Taylors themselves did not include Harty in their exhaustive and definitive gazeteer of Anglo-Saxon architecture. Confusingly, the Church Guide (which is excellent) then goes on to talk of “The early Norman church”. The entrance to the Lady Chapel is a relocated chancel arch and there is a filled-in Norman window above the arcade. So Norman work is undeniable. Is there sufficient evidence for a pre-Conquest foundation? I think not. Or is this a case of pre-Conquest construction techniques surviving for a short period after 1066?

The north wall of the nave was pierced to accommodate a north aisle of about AD1200. “Pierced” is the right word because the arches are unadorned by mouldings or capitals. There is also a filled-in Norman window. The chancel was also replaced in the thirteenth century. A Lady Chapel on the south side was added in the fourteenth century and the vestry to the north was surely also originally a chapel. Then we have the usual motley collection of Gothic windows that don’t really deserve too much attention!

The little bell cote is quoted by the Church Guide as being fifteenth century. It is undistinguished as most bell cotes are. What make this special is the timber framing that supports it, resulting in a striking arrangement of timbers at the west end of the church.

The most remarkable thing here is the chest, safely locked away behind a gate to the Lady Chapel. As it was stolen and recovered at an auction house in August 1987 we must not criticise the church for keeping it secure! It depicts in great detail a jousting scene. I do not think “stunning” is overstating its impact. It was a muniments chest, designed to keep title deeds and other documents safe. It is thought to be Flemish (a “Flemish Kist”), and of the fourteenth century, both of which I am ready to believe. It is also said to have been found floating in the Swale Creek which I put firmly in the box containing the story of Edward Shurman and his horse at Minster-in-Sheppey! On the opposite side in the Lady Chapel is what the Church Guide refers to as an altar table, possibly from Meopham Church. Pevsner seemed to think it was a composite piece and did no mention it as an altar table. But he also said - as the Guide does not - that it is edged with figures of “monks”. They seem to have extraordinarily luxuriant hair to have been monks, so I have my doubts. Furthermore, altar tables are a post-Reformation thing, Would one have had figures of monks when the monasteries had been so comprehensively suppressed in England? So, in my view, it is mystery - but a very nice one.

Then there is the stained glass. It is unapologetically modern, rather gorgeous and most of it designed by parishioners. It is one of the best features of the church and it cements it as a building built, endowed and loved by its community.

This is a church for the connoisseur who has the eyes to see something beautiful in its simplicity and who can absorb the spirituality of a building that has served its isolated community on the maritime edge of Kent for a millennium. It is one of the best-loved churches I have ever visited and I happily count myself as a member of its fan club!

By the way, I must mention potentially unique about this church - or a least a great rarity - that even the excellent Church Guide does not mention. I cannot think of another church that has not an inch of paved footway around it! Not even a bit of gravel. How nice and rural is that? Remember where you read it first. And bring waterproof shoes.

Left: Looking towards the east end. To the right of the screen is the archway to the Lady Chapel that contains the church’s treasures. Right: The arcade to the Early English north aisle. Note the plainness of the arches cut straight through what was the outside wall of the nave. Note also the comparative thinness of the wall suggesting to some that the nave was of pre-Conquest origin. You can also see the filled-in window. The rood screen is rather spare but fourteenth century.

Left: Looking towards the west end. The lack of a west tower allows an unusually large expanse of glass so this is quite a light and airy church. Right: The very attartive modern stained glass in the west end. Click here to see several pictures of the Harty stained glass.

Left: The fourteenth century “Flemish Kist”. The locked gate mean that you have to push your camera through as far as you can and thank heavens for having an articulated screen to view it through. It is said that this is a just-for-fun jousting contest. The knight on the left is about to hit his opponents shield with his lance. The knight on the right has broken his. Each knight has a squire in attendance. It is not clear what they are holding but they may be spare lances (Sir Rightie is going to need his) because both are holding something that seems to have been broken off. Sir Rightie’s squire seems to be standing on a fallen tree trunk. Surely not? Note the leg guards on the two knights and Sir Rightie has spurs. For a larger picture click here. Right: This picture shows the extreme right of the scene where a man stands under or within a castle turret. You can just about make out a little of the left hand panel which is very similar but which has larger buildings with lancet windows.

Left: This table faces the chest in the the Lady Chapel. It certainly has the dimensions for an altar table but, as I said previously, this seems most unlikely. Right: Part of the timber framework that supports the bell cote.

Left: The timber-framed north porch. Centre: A somewhat incongruously ornate niche of perhaps the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. Right: A Norman corbel.

Left: The church from the south/ Note the blocked up doorway. It would be more usual for the north door to be blocked: the “Devil’s Door” or more prosaically the one facing where the coldest weather came from. But the south side of this church faces the Thames Estuary so I am guessing that is the direction where the worst weather was coming from. Right: The church from the south east, the estuary just visible in the background. Even the vestry which is almost invariably on the north side - which in many churches contributes to a more accurate description I sometimes use as being the “Ugly Side” - is on the south side here. I have to acknowledge, however, that it was built in the fifteenth century so it was not built as a vestry. Someone academic should do a thesis on why vestries of the last couple of centuries were designed seemingly with ugliness and architectural inappropriateness as their main attributes. It’s a good job perhaps that most are put on the north side with the boiler houses, bins and over grown gravestones.